Editor’s note: though poet Shankar Narayan and artist Monyee Chau come from different cultural backgrounds, their work addresses similar issues, including resisting cultural assimilation. They’ll both be participating in the event “Seattle Writers + Artists,” 6:30 pm, Tues. December 10 at Vermillion in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood.

.

Unbordered

there is the border

there the border remains

border between country and country

border between body and body

border between myself and those

i have violenced in the name of manhood

border between myself and my

vulnerability

within others’ borders

i search myself

between anger

and man

between spoken

and unspoken

all these abstractions

unfit for poetry

how i long to be genderless

beast in genderless world

where woman and man are synonyms

for each other and for perfection

if this poem followed form i’d turn now

to talk of breaking borders

but when have bodies

ever followed form

when have borders ever freed us

to choose our vessel

.

.

Christmas Tree

Because I’ve read the history books I’ve seen

this picture—find a beautiful thing and celebrate

by killing it. Bring it into your dominion

and watch it slowly die—that is the story

of my country, after all. I have never settled

though I love the hayride, Cascadia’s winter air so clean,

so different from the Delhi I left behind, my friend’s hair so golden

in the impossible sun, her children giggling, that I almost feel

what it means to be a part

of something. But to be colonized means never to recognize

belonging—so when you feel something

like it you question, wonder if that voice rasping outsider, outsider

really means it. And then the blade, the hacksaw

to the tree hunkered into the curve of the hillside, and when we choose

it we choose it for its perfection, though the voice resists, says No,

don’t be so beautiful, because it seems blameless

like the peasant so exquisite she draws the king’s

eye, and he points to her and says That one, and after his procession

with its stallions and imported elephants the guards come, drag

her from her hovel as she wails, but her father and mother do nothing

because helplessness has colonized

their bodies from deep inside, and now I too have failed

to speak up again. It is too late

for this little pine on this hopelessly gorgeous day in which I am losing

myself on this radiant hillside, radiant

as the queen in her marriage procession, freighted

in emeralds and conquest diamonds, perfect

even if she does not smile—and it’s possible, even if I do not remember,

that it is my own hands that seize

one half of the hacksaw, and it is my own back that bends to the grim

work of severance, of drawing in the teeth, jagging first through unresisting

bark, then deeper and deeper through xylem and phloem and into the deepest heart-

wood, and who knew that felling a single spindly tree

would be so difficult, but if nonetheless I put all my might into the killing

it is because my friend’s smile glitters on the other side

of the blade, I sap all my strength to do this, though I can see

the future so clearly, after the tinsel, the lights, the ornaments

hung one by one, each with a history,

after I am encircled in the glow of this family who love

me, then the icy curb where the pine lies

on its side, stripped of all adornment. And I will go back

to my cold living room which I have tried to warm with my own

small tree with tiny lights that shine when plugged in. It sends its burn

so deep inside me. It’s fake, though.

.

.

.

Kurta

For three weeks of each year I am

my other self, meaning my real

self, meaning I’m trying not to lose

track of how many skins I’ve shed. Doesn’t the body

know—no matter how you cloak,

some things feel home. Hence this thin

cloth, the length of one stride, this body

was born for—lean and long, centuries

of hunger and heat reflected like mirage

in its flow, no losing limbs

in Wal-Mart lumberjack flannels

as I have been lost for twenty-five years,

in this cloth I find myself spun, though

many who think they know me won’t recognize

the self I find. I am always arranging my body

as others want it. I have wandered

years in suits like snakeskins

though in my heart I am the mongoose, I have never knotted

a tie that wasn’t slowly choking

me, conscripting me into uniform the British

refused to relinquish when they colonized

our bodies. And what body can forget

erasure, erase empire? The churidar caresses

my leg, tight to skin like mother and lover, secretly defeating

hazy air of all the throne rooms I trudge

to find signs, visa or green card dropping from sky. Here

I wear more colors than a single iris can hold,

even if I cannot say why I wear mostly black

in my other, American life, black that is the absence

of color. Instead I make of my body and yours

something new, absorbing

like red dye the greatest joy of every stranger

who crosses into your land

and becomes you—in our brown

empire we grow together, and together

we are reborn. This is how we colonize—let there be

turquoise, vermillion, saffron,

lapis lazuli, iridescent dragonfly, changeless

diamond, satrangi. This rainbow

becomes you. Kurta, hold us

here. Here we turn all

colors. Here in your embrace

I will breathe.

.

.

Diasphoria

Never changed my name. Not to John, not

to Paul, not any other goddamn apostle. Never

understood. Why? Never

needed four horsemen. Never

grasped in graspy immigrant hand someone’s twisted

antiquity. Cognitive phonics, turbaned

Sikh in Birkenstocks, backpack with twang. Never changed

names. Never saw assimilation half-

cooked, half-consumed, half-cocked. Did she mind

wrapping her mouth around this name? Never

got Siddharth to Sid, prince of peace

to cat disease, never changed to Shaun no

matter how much shit. New country—one

syllable all the slot you get. Rohit lops off

an appendage, runs for Congress—all the polls

agree. So much in a name, check-

box familiar, comfort close at hand. My name lack

of human. Someone changed

it anyway, easier than trying,

people should know better. Seen me twenty years. Surrounded

by Andrew, internalize Judas. Years later know

what a name is. Years later Bobby and Nikki add color

to bloodless coup. Hear twang, feel

shame. Where’d you go,

Piyush and Namrata, ejected

from beauty contest neither black

nor white, checkmate, too late? Leave inconvenient

Hindu at churchhouse door. Some Catholics are Shivas,

some violence wraps flaming mouths

around my names. God of destruction—who

is here, who is there, who never left, I never

reclaimed. Didn’t need to. Diaspora

is dispersal to sixteen winds

is born name not one you want

is country when too many shed names

hide like tigerskins of creatures

you once were. Apocalypse

reflecting in eye glass. Never

stopped being beast.

.

.

Artwork by Monyee Chau, Lunar New Year photographs are a collaboration between Monyee Chau and Alexandria Britt.

Monyee Chau’s notes on the images:

My Family’s Apple Pie 2019

digital illustration

dimensions vary

If You Don’t Share The Dog’s Head With Your Children… 2017

found cardboard

5’ x 7’ x 2”

This is an old country Taiwanese saying my grandfather shared with me. I wanted to recreate it in a way that expresses the fragility and possible ephemeralness of stories. I wanted to play to racial stereotypes while showing that these things were put on our people for the sake of survival.

Gung Hei Fat Boi 2018

Collaboration with Alexandria Britt

photography

dimensions vary

This is a self portraiture series to queer this strange life of a new identity for Asian Americans influenced by their heritage and by westernized culture and questioning it through the culturally important day of the Lunar New Year.

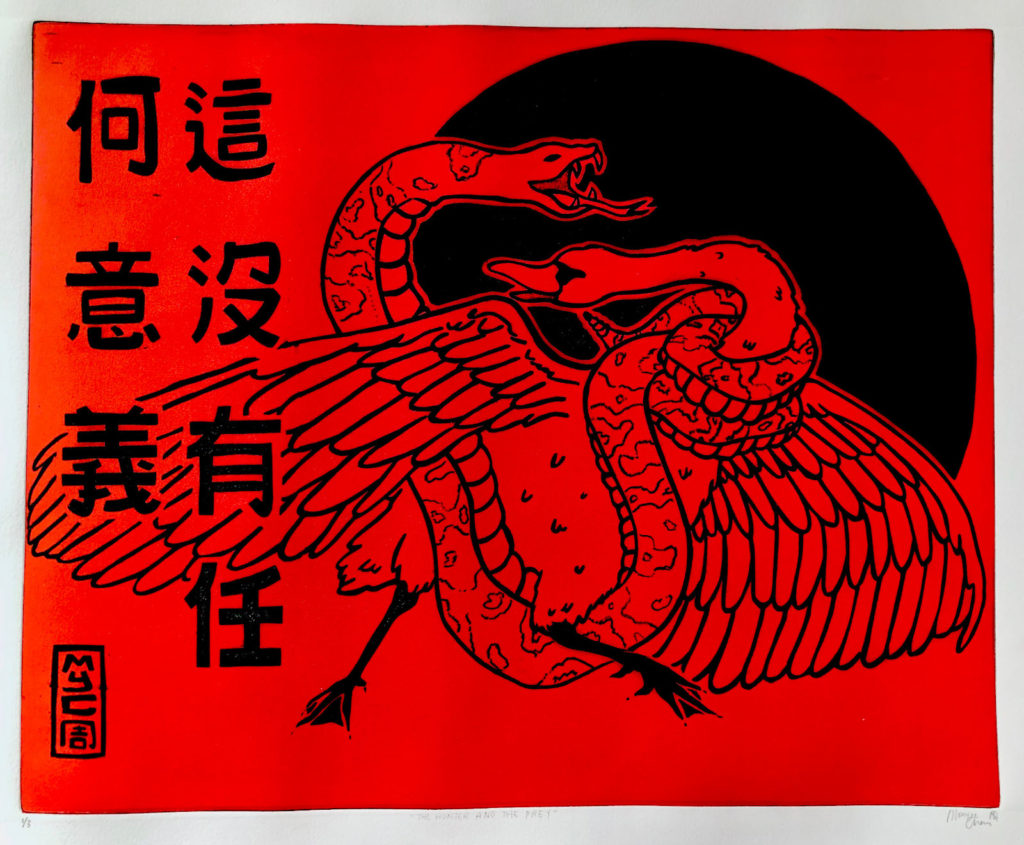

Hunter And Prey 2019

vitreography on rives BFK

22.5” x 19”

In this piece I wanted to play with the audience’s expectations of what they have of my work and expect heavy symbolic meaning as a lot of Asiatic work does. Eastern imagery being shown with characters often sparks the inevitable, “Wow! What does it mean?” The translation says: “This has no meaning.”

Publication of these poems and art was made possible by a generous grant from the Seattle Office of Arts & Culture.

Shankar Narayan explores identity, power, mythology, and technology in a world where the body is flung across borders yet possesses unrivaled power to transcend them. Shankar is a four-time Pushcart Prize nominee, and is a recipient of fellowships and prizes from Kundiman, Jack Straw, Flyway, and Hugo House. He is a 4Culture grant recipient for Claiming Space, a project to lift the voices of writers of color, and his chapbook, Postcards From the New World, won the Paper Nautilus Debut Series chapbook prize. Shankar draws strength from his global upbringing and from his work as a civil rights attorney for the ACLU. In Seattle, he awakens to the wonders of Cascadia every day, but his heart yearns east to his other hometown, Delhi..

Monyee Chau is a Taiwanese/Cantonese American artist residing in Seattle. They received a BFA from Cornish College of the Arts, and explores the ideas of decolonization and ancestral healing through labor in multiple processes of art. She is passionate about redefining the experience of being a second generation immigrant in America, and building community through shared food and storytelling.

.

If you appreciate great writing and art like this, please consider becoming a supporting reader of Cascadia Magazine at our donate page. If you’re already a supporting reader, thank you!

One comment

Comments are closed.