.

.

It was early, Denise and I were still in bed, hadn’t yet spoken, and this was the question chosen, the first thing said, to initiate both of our mornings:

“Were you having trouble breathing last night or something?”

I gave a little half-shrug that I often thought was adorable, but there was no indication that it was received like that. I tried to stop looking cute and attempted to speak in an adult-sounding voice—not the child-like voice I habitually used with Denise.

“Not that I noticed. Why?” Denise sat up and pulled a t-shirt on. I watched breasts disappear and I was disappointed. Even though those breasts had become like strangers to me—for the past year, in addition to avoiding pronouns or using they instead of he or she, Denise asked me to pretend they, the breasts in this case, didn’t exist, to not touch them anymore, to not sexualize them because they were confusing and I obeyed because I loved and respected Denise and also because it felt sexy to have something that I couldn’t do—it still felt as if by putting that shirt on, Denise shut the door to sex.

“You were doing that thing where you kind of chortle and breathe through your mouth again. It sounds like you’re choking.” They slammed the covers to the side and roughly got out of bed and in the process their fist sort of hit my hip bone. It hurt a little but I intended not to feel it since Denise hadn’t noticed that they’d done anything.

“Sorry about that,” I said. I put a t-shirt on and covered my own breasts, aware that no one was sad to see them go. At the end of the bed, Denise stopped abruptly as if inspired.

“I can’t imagine living with that sound for the rest of my life.”

There was no sense of remorse in that face, probably because it was so full of truth. I do make a weird sound at night and what I wasn’t brave enough to ask Denise was, wasn’t it worse during the day when my nose made a fairly regular whistle on my exhale? When I was 21, I came out and my mom—overcome by shock or rage or what she thought she was supposed to do—popped me quickly in the nose. A snap of the wrist and I remember that as I covered my face her hands went to her mouth. She let out one sob then said, “I don’t know why I did that, I’m totally fine with this.” I don’t remember what we told the doctor at the hospital, maybe that we were gardening and I walked into her elbow.

“Do you want to help pay for a surgery to fix it?” I asked.

“I got my own body to worry about,” Denise said sharply and it was so early it sounded like a shout. I slipped out of bed and stood on my tiptoes. I was expecting a long fight, and I wanted us to be on equal footing, I wanted Denise to look into my eyes, which didn’t happen. In an instant Denise broke up with me.

“I’ve been thinking about this for a while,” they said.

“But I haven’t.” We let that statement in its powerlessness hang in the air before it dissolved under the high-pitched hiss that escaped my nose, which I wished I could tear off and throw at Denise, who wouldn’t even talk to me, wouldn’t give me an explanation, who said I was being petty—wanting closure, wanting an explanation. It was capitalist, they said, of me to want a reason. Denise had this ability to be so stoic no matter how upset I got. In the bedroom that morning I screamed:

“What do I need to do to get you to respond to me? Do I need to like shit right here in front of you? Right on the rug? Like an animal?”

I moved like I was going to pull my pants down and even though Denise was looking at me it wasn’t like they were seeing me.

Obviously, I didn’t do it. Denise’s best friend Del came by with a truck and by the evening carted them and all their things away.

If most pronouns are already an interruption of your intimacy because you are speaking about someone in the third person, rather than to them in a bed, that sense of plurality, that singular “they” asserts even more that Denise doesn’t belong to me and never did. This is capitalist. I know this.

The last bit of communication I received was a postcard (a picture of our town’s waterfront) asking me not to reach out or contact them. Denise said we needed to take 90 days and the only soft thing written in this letter was that they thought the 90 days would help me let go and heal.

As an aside I want to say that the pronoun thing wasn’t that hard for me. It’s only awkward when I’m around other people who think it’s weird and then it’s hard to use it, otherwise now I’m tempted to default to they in all cases—even people who I know use traditional pronouns go through a filter in my mind. But I will admit that the thing that’s hard about telling this story, with using they right now, is that it puts Denise even further away from me. If most pronouns are already an interruption of your intimacy because you are speaking about someone in the third person, rather than to them in a bed, that sense of plurality, that singular “they” asserts even more that Denise doesn’t belong to me and never did. This is capitalist. I know this.

I’m sensitive about being recognized as queer or radical. I have to make a constant series of conscious decisions and I still have to come out, multiple times a day; so I don’t just wear the barrette, I attach the turquoise giraffe-shaped fascinator and purposefully make my mascara run. Once, just to go to the coffee shop, I spent hours working my hair into a beehive. I wrap fur around my shoulders in the grocery store. I flirt with all the butches and studs and the ones who prefer to be called masculine-of-center even when I don’t really want them because there is little more satisfying than watching another queer’s shoulders soften and smile at me excitedly in that open mouth way once they know.

I’ve always dressed this way though, even before realizing I was queer, and it was actually when I first came out that I denied myself in any way. I tried to look moody, morose, and wore little boy clothes to parties with white queers where I scowled and tried not to say much unless it was concurring with some judgment over a person under the guise of condemning a system. No to marriage, yes to labor rights, no to make-up, yes to thrift stores. Yes to smelling a little dusty. Yes to looking mostly male. The party when I met Denise is where all my stoic butch stuff began to fall apart. I don’t even remember what Denise said, but it was funny and it’s possible that I was so starved from my own personality and so desperate to express something that it really was only mildly funny, but I let out a squeal after the joke and everyone looked at me.

“Oh Lord,” I said, folding over to prevent all of me from spilling out. My voice was loud, within full range, my nose whistled.

This didn’t really get anyone else laughing, most eyed me suspiciously, but I remember Denise smiled, and it was playful, exposing, and extended out in the room like an offering of friendship that I snatched before they could decide otherwise.

It began subtly. We planned to ride bikes together to the next party and Denise showed up with two party masks, both hot pink with a wild display of feathers, but one was also covered with sequins and this was the one that they thought I should wear. I remembered a pair of hot pink tights I’d abandoned, that my mom bought me once for a Halloween costume and I pulled them on and put a pair of torn up jeans over them. At some point over the course of the night, I removed the jeans and wore the tights as pants, and though many of the faces remained stoic quite a few of them turned to grins.

Then, on a trip to the bins, I found a leopard print bustier, the wiring a bit warped but in otherwise good condition.

“Look at this,” I said to Denise. “It’s disgusting what women have trapped themselves into.” I held it up with a finger and felt proud that I had thought of something to say that could be applied accurately, and that I thought I kind of agreed with. Denise looked at it, then looked at me, and just as that smile had been so revealing, their eyes too showed what they imagined. And it was me. I knew it was me.

“Yeah, but I think it’s kind of sexy.”

I added it to my bag and that night I biked to Denise’s house. By the time the door opened I’d pulled off my jeans and stood in the bustier, the pink tights, and the mask. My hair was teased like ’80s metal. Denise didn’t smile, but those eyes were the same as that afternoon and I knew I fit into some place in their brain that they wanted externalized. From that night on I externalized it for Denise. But if they didn’t want it now, what was I doing?

It’s hard to do 90 days in a big city. I’d read novels set in New York where lovelorn characters split up the city, but how do you split up in a small town? I didn’t understand what here belonged to either of us. There was a downtown strip with hunter-run bars and some gems in strip malls—the Asian grocery, a pet shop window with puppies in it, an antique shop with quirky records—but not enough to split up and claim. I’m either a little bit psychic, or ruled by fear, and it was difficult to determine which was speaking the first morning I felt emotionally capable enough to get out of bed and go to the grocery but couldn’t get the car to go in that direction. It was almost like I could feel this presence that was Denise; the force halted my car and even though I pressed my foot on the gas I couldn’t really move. I did the witchy things I learned from other white queers that were appropriated from cultures they knew no one in: burned herbs around myself and my car, made a little altar with bird bones and feathers on the dash, but maybe that’s where fear stepped in because even if I was waving that bundle of smoke in front of me it didn’t clear a thing. I wasn’t certain which friends were mine during that time but I tried calling different people to test it out during that month, mostly out of desperation so that I wouldn’t starve to death, in hopes that they were hitting on an errand that might serve me. I’d test it out first, “Hey—would you mind picking me up milk and a bag of rice?”

“No problem. Do you need anything else?”

“Well,” I’d say glancing into my refrigerator, “since you asked.”

This was how I wanted the interaction to go, but typically no one answered, or if they did I got off the phone angry, feeling it would have been better if they hadn’t answered at all and wondering why, for instance, Jasper answered just to say nothing, which drove me to ask in a kind of panicked way, “Could you pick something up from the grocery for me?”

“I can’t,” Jasper said, voice husky, intentional, pretending not to be awake yet. “I have band practice.”

“Maybe you could take me after band practice?”

“Meeting with that prison reform group.”

“What about after that?”

“I don’t know when after will be.”

What was the point of being in community if you could be so easily thrust from it?

I didn’t want to mention any of this to my mom so for a month I ate what was left over in the apartment—lentils, chickpeas, oats, and dry cereal—and what was left from the garden outside, Denise’s garden. I’d watched from the kitchen as Denise lifted each plant out of the earth like nothing had contained them there, as if they had just chosen to be there and now chose otherwise. All that was left were salad greens, probably because they were too difficult to move, and a few varieties of edible flowers: borage, violets, and bitter calendula.

I ate these things and looked at myself in the mirror, in sweats, my hair down and loose. I didn’t feel like a femme, or a she, or a he, or a they—I was no gender. I put my hand on my jaw while I chewed and felt it rise and fall as I watched the reflection on the opposite side.

“Can I exist in relation to myself?” I asked out loud. My voice sounded hollow and I didn’t have an answer.

At around 35 days I felt something clear, it was like what I knew of Denise had disappeared—picture a body, like in a cartoon, giving a slight pop as it evaporated in a puff of smoke—and I was so overwhelmed by grief that I went out to the garden and pushed my hands in the dirt just to feel something give and yield. It wasn’t that the ache I felt for Denise was gone, but as if my experience of them was totally gone from the world, or cut off from me and I wondered if what I was really picking up on was some date Denise was on, and maybe that’s what I would have said if anyone would have asked, even though I knew on some other level that it was more than that.

I got in my car and there was no black force or presence, nothing kept me from anything, and I walked right into the grocery store, a bit stunned, and purchased chocolate milk. I felt a kind of empty power course through me as I sipped it staring at the slow moving puppies in the window. The Asian grocery had closed since Denise left and a hipster record shop had replaced it. I felt guilty going in there, even as I listened on headphones to Del’s new record and used the reflective back of the CD cover to apply more eye liner. I strolled into the coffee shop, a space I thought I wouldn’t walk into again, and familiar faces looked at me and sort of saluted and I felt a surge in my existence. In that moment, my hand shaking as I paid for my coffee, I couldn’t even remember the name of the person I mourned. I shook my head and the barista, who I knew peripherally looked startled and maybe a little afraid so I smiled, turned away, and would have left if a group of folks I knew hadn’t waved me over.

“How are you?” one asked. I bit the lip of the coffee cup then looked at the imprint my lipstick left. I wasn’t sure if I could say anything without sobbing, I felt so strange.

“How’s Denise?” another one asked and someone elbowed this person who kind of snickered, and I swear for a very brief moment I paused at the name.

“I don’t know,” I said. “We’re not talking.” Someone snorted and they returned to their original conversation for which I had no context so I left without saying goodbye. This was how the town had been divided. There had been nothing keeping me from the grocery store—of which I nearly developed scurvy from the lack of visiting. I could move anywhere I wished, but the friends wouldn’t be mine for a while.

When the 90 days were over I tried calling Denise once. The voicemail was changed—there’d always been something, sort of a cute and fun recording like, “Tell me what it means to be Denise.” I loved that recording and I always took advantage of it and said it meant being sexy and strong and kind—that it meant having great thighs and an incredible tongue. This time it was just an automated voice stating the phone number. I felt panic rise—I didn’t know if I should leave a message and thought maybe the sound of my voice would be too upsetting so I left a message in what I considered to be a British accent.

“G’day! This is your old friend Ana. Been a bloody long time. Miss talking to you, chum.” Then I paused because I wanted to say I love you in a normal voice and still didn’t know how to say goodbye without it. So I just hung up. I didn’t hear back and I didn’t call again.

Having gone through it, I think the 90 days thing is mostly so the community can reset itself. To get used to having two once-partnered people reenter the group with a somewhat clean slate. It was kind of like being part of an outdated web browser on an old slow computer that you don’t have the money to trade in, but the page always refreshed eventually, and maybe the relief in the end outweighed the frustration. The web browser refreshed and Jasper invited me to the prison reform group and we made out afterwards in the parking lot. Then the barista asked me on a date, and the owner of the record store, and the teenage boy who bagged my groceries. I was asked on so many dates and even sometimes I would be on a date and get asked on another one. They always asked me at some point how Denise was, if I’d heard from Denise. When I said no they would smile, and maybe try to see how many fingers they could put in my mouth.

When I was twelve my Italian grandpa took me to his Knights of Columbus Hall—they were offering ballroom dance lessons for grandchildren of members, but I was the first grandchild that arrived. I remember the way the other grandfathers smiled when they looked at me, and at the time I didn’t interpret it as pervy. The room was warm and blue with cigar smoke. My grandpa lit a cigarette as he set the needle on the record player while the other men spread into a circle. I danced with one man in the center, and I felt like I was coasting on ice, my feet barely touching the floor, and then I was passed to another man, and then to another, spinning and spinning until I’d danced with everyone in the room.

How to explain the thought of someone not wanting you anymore? How to describe someone erasing you with the same pencil that drew you, leaving only your paws?

A little over a year later I ran into Del at the grocery. He seemed to be deciding between oranges based on their heft, one in each hand, and greeted me warmly. I responded in kind and I was so amazed that I didn’t feel a twinge or fear and that Del didn’t seem to either.

Del’s band had been on tour for a while and now they were finally settled back in town. They’d actually made some money so he was able to take time off for things like determining an orange’s merit by weight.

“I wish this is how it could always be,” Del said tossing the orange into the cart. “I feel like the person I’m supposed to be.” He gave me a very dignified and respectful glance up and then down. “You’re looking like a fox.”

Del meant literally. I had just died my hair a carrot red with some brown stripes along the side and I had styled it a mix of spiky and long. In addition to my fur shrug I was wearing black pleather leggings and boots that I’d painted to look like back paws. I looked down and adjusted my fur.

“I haven’t talked to Denise for a while.”

Del didn’t say anything. He picked up a mango and sniffed it.

“I was wondering if they moved out of town, or something.”

“Look, he’s probably going to be pissed at me but go ahead and tell him that I did this.” This would usually have been a familiar indication of what was going on; in community I heard this all the time, but in the moment I’d forgotten all my politics, was completely daft. He reached into his pocket and wrote down an address on an old receipt.

“He’s been trying to be private about things. He goes by Dane now.”

I looked at the address. He was living in the country, at the edge of the town, which seemed unsafe to me.

“He wanted to tell you but he wasn’t ready yet.”

“Does anyone else know?” I asked. Del pressed his lips together. I thought of my grandpa’s lips on his cigarette as he moved the record player’s arm.

“Yeah.” He lowered his head briefly and then reversed that movement and lengthened his spine. His full height. I’ve come to recognize this as the action a progressive person takes before trying to reason with you.

“To his credit, he really got mad at folks when he found out they were asking you where he was, which was partly why he moved to the country. His thinking was if this community was just gonna act like any small town, he didn’t want to be part of it.”

“They were making fun of me?”

“They were being assholes.”

I pictured the men in the meeting hall spinning me but replaced with the faces of my gender queer dates, laughing at me, gnawing on this secret while they slid a hand up my thigh.

“He has a new number too. Let me text it to you.” I watched Del’s fingers slide across the screen of his phone like they were moving through heavy cream. I squeezed a mango so hard I put my thumb in it. I buried it beneath the others.

I went outside to a pay phone and dialed the number, knowing he wouldn’t pick up. The voicemail clicked on and even though his voice had a deeper drill-whine to it I could still make out the familiar, tender, cadence.

“Dane’s not here but Dane wants to know what’s up. Dane wants to take care of your needs.”

I hung up. The last part of the message made me think of him dating other people and it was like no time had passed and I hadn’t fucked everyone. I felt sick. How to explain the thought of someone not wanting you anymore? How to describe someone erasing you with the same pencil that drew you, leaving only your paws?

We could perform gender with such extreme attention that every heterosexual would see us and not feel straight enough or every gay man from New York would see us and want to buy property here immediately.

The house looked nicer than I expected. There was a vegetable garden planted out front growing our tomato plants and a row of collard greens. A swing hung on the porch and there was a tool shed at the side of the house where a wheelbarrow rested against the frame. I pictured him on his own on Sunday mornings, happily wheeling compost, or dirt or weeds around, wearing thick gardening gloves. He must have loved the day when he purchased that wheelbarrow.

I walked onto the steps quietly. There was no way he could hear me. I’d worn sneakers and jeans. The only thing mildly spectacular was a brass belt buckle with the silhouettes of two horses. My hair was limp at my shoulders. He’d have to at least level with me if I wasn’t dressed like an object.

He opened up the door before I knocked. He wore slacks and a dress shirt, the sleeves were rolled up but he wore a tie. His hair was still buzzed and the skin on his face looked a little rougher, a little dry from shaving. I was looking for things. The shifting. He was beautiful.

“What a great outfit,” I said.

“Thanks—I’m technically at work.” He looked at me carefully, and I couldn’t place myself in his gaze like I had before.

“I recognized your footsteps,” he said. We didn’t hug each other, though I wanted to and felt a frustrated, capitalist sense of longing that translated as anger.

“You must love your wheelbarrow,” I said. He stepped out to look around the house. He was barefoot. He smelled like perfume.

“That’s my landlord’s.”

“Do you use it ever?”

“Maybe eventually—I’m still healing.” He rubbed at the corners of his chest. I couldn’t help myself—I looked. His shirt was thin and there was nothing to bind him underneath.

“When did all of this start?”

“You know better than to ask that,” he said.

“Well, at least some context?”

“Do you want to sit on the swing?” he asked. I shook my head.

“I get nauseous on those.”

“Let’s sit in the doorway.” It was narrow and it felt strange to have any part of my body pressed up against his. I felt his heat and I wanted him like we had never broken up or experienced 90 days, let alone a year of no contact. If this was a great experiment I had failed.

“I got a prescription for hormones the week before we broke up. Took my first shot the night I left. I got this great remote programming job, so I’ve been able to pay for everything and I had surgery three months ago. Del went with me. A couple folks pitched in. I still have to send thank you notes.” I rubbed at my eyes like I might cry but I didn’t. I felt a swirl of panic inside of me.

“I want to ask why you didn’t tell me but I’m afraid you’re going to say that it isn’t my business or that it’s not mine to ask about or some other kind of stoic bullshit.” I covered my mouth the way my mother had.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I just needed to make this decision on my own and not discuss the act of making it. Not process it.”

“Have you been dating anyone?” I asked. I expected another femme to come walking out of the house wearing an apron, a pie in each hand.

“Yes.”

“I can smell her perfume.” I said. He turned his head and looked at me for a long moment and I wanted to push his face away but I was afraid to touch him.

“That’s mine,” he said. “Essential oils. I’m not really into femmes anymore.” He gestured to me, it may have been inadvertent but he still did it. I watched him catch what he’d done. He started playing with the hand that did it.

“I’m more into being with someone masculine, like something equal. It all changed really fast.”

He reached down and hooked on to his big toes.

“I think it’s good that you’ve been dating though,” he said.

“Everyone’s been making fun of me.”

“They weren’t making fun of you, exactly. They were testing to see what you knew so they didn’t say anything I didn’t want them to. They were just trying to be mindful of what I was going through.”

“Because you’re masculine and worth more than me?” I snapped at him.

“Look at where I’m living. Don’t pretend like you don’t know what could happen to me. I just don’t want anyone else’s opinion on how to do this. Sometimes I crave it, but I kind of want to do my own thing and not hear from anyone about what this is supposed to look like, how I’m supposed to act, how other people should act around me. I just want to garden and work this job.”

I exhaled and there was a whistle. I coughed and tried to breathe through my mouth.

“You can breathe through your nose. I missed that whistle.” My nose let out a high, sharp whinny and I wished it hadn’t accommodated him like that.

“Are you suddenly nice now?”

“Probably not,” he said, and he looked me straight in the eye. “But I’m happier in a lot of ways.”

“From the transition or not being with me?” As soon as I said it I wished I hadn’t.

“Probably both,” he said.

I stood up and walked calmly over to his garden. I looked at the happy, tall plants and rested my hand on one of the tomatoes. I wasn’t sure whether to leave or stay when I felt the plant kind of pulse under my hand. I looked at it and it trembled, probably because my hand was trembling but I felt this phrase in my brain, take me, and it wasn’t coming from me and I felt something like permission when I pulled the tomato off, heavy and green in my hand. I took a bite of it and looked at Dane—he didn’t move. I undid the twine from the support and pulled the plant from the ground. The dirt fell away easily as it had when he pulled this plant from our garden. I laid it down. I pulled out the next plant. And the next. I finished eating the large tomato and then pulled out a cherry tomato plant and held it up in the air—freshly out of the ground, a sacrifice, its roots dangling, and I stared at him while I reached for a tomato, plucked it off, and put it in my mouth. The tart acid exploded and I felt my eyes squint but I didn’t stop looking. I ate all four of the small tomatoes—each one felt like a bite of power—and then dropped the plant to the ground. He still didn’t move, I just couldn’t believe that he could sit there like that and not even stand up, not give me just any kind of reaction, some sense that he was feeling something, and that was when I undid my buckle and squatted in his garden. I focused my breathing and fixed my eyes somewhere past Dane who, believe it or not, stood up.

“What are you doing?”

I grunted and grit my teeth. I pushed. Wind whistled out of me. I reached back and spread my cheeks apart trying to coax out the small pellet I knew was lurking in there. He took long fast steps toward me but he didn’t know what to do. Just looked at me and then my ass, his weight shifting, I could see him measuring whether he should push me over, whether that was a cruel thing to do. I wiggled back and forth, and the turd fell to the ground with barely a whisper. It was small and dry. I pulled up my jeans and kicked my legs back, spreading the scent or covering it with dirt, the way a fox might. My nose whistled. Dane looked into my eyes and I saw that his were brown. Had I mentioned that? It was like I hadn’t noticed until that moment because I’d been so focused on what was behind them and maybe I saw him seeing me or maybe I was finally seeing him.

“That wasn’t okay,” he finally said.

“I know.” I finished buckling my belt. “Report me to the queer board of directors. Get me demoted to lesbian.”

“The lesbians wouldn’t take you,” he said. “You shit in people’s gardens and wear real fur.”

“Only when it’s used,” I said.

He knelt down and covered it with dirt, his hands moving carefully, as if it were a seed but even planting feels weirdly like a burial. His voice got appropriately soft.

“All we had in common was that we liked how wild-looking you could get. It was like dating an animal and for a while that was perfect because it made me feel like an animal and what does an animal care about gender? You really performed it and I wanted to do that too. I couldn’t figure out how to perform and be with you—I didn’t want it to be playful. I wanted it to be serious. I think I’m a very serious person and might want a husband and a MBA or something.”

A truck turned down the road, the first vehicle since I arrived and it crawled slowly past us. The man raised his hand and we raised ours back and he watched us in his rearview mirror, making sure there was no cause for trouble.

“I know, the queer board will vote me out for that,” he said.

“More likely the rest of the world will vote you in,” I said.

If I hadn’t shit in his garden maybe I would have tried to plead the point that we just hadn’t discovered what we had in common but that here we were, on the brink of it, and if he let me live in that house with him I would make pies all day and he could fuck me when he was done with capitalism at night and I’d call him my man or I’d wear a suit and buy a dick and show up like a hook-up and we could flip that house together and open up a record shop in a part of town that didn’t need a record shop. We could perform gender with such extreme attention that every heterosexual would see us and not feel straight enough or every gay man from New York would see us and want to buy property here immediately.

But I did shit in his garden and it revealed some things to me: that I was an animal in his eyes even before that, and that the world would bend away from me even if I wanted to bend toward the world.

So instead, I knelt down too, said:

“I’m glad you made the decisions you needed.”

He lowered his head and I lowered mine, because if he was preparing to reason I didn’t want to see it. Take a picture, because for this one moment it appeared like we were bowed, equally for once, toward each other.

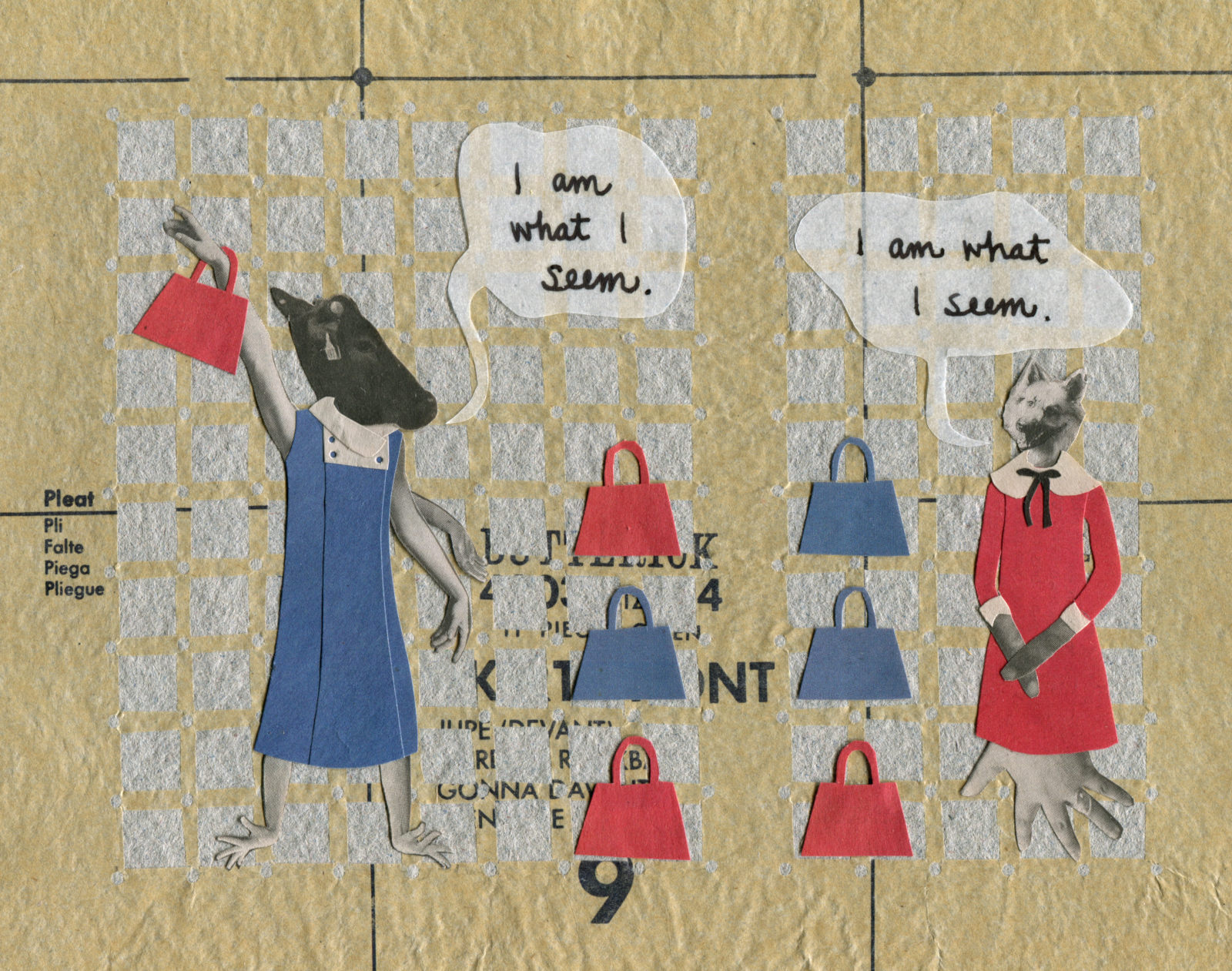

Image by Mita Mahato, used with permission of Pleiades Press.

Corinne Manning is a prose writer and literary organizer. “Ninety Days” is from their forthcoming collection of stories We Had No Rules (Arsenal Pulp, March 2020). Their essays have been anthologized in Toward an Ethics of Activism and Shadow Map: An Anthology of Survivors of Sexual Assault. Once upon a time Corinne founded The James Franco Review, a Seattle-based project that sought to address implicit bias in the publishing industry.

Mita Mahato is a Seattle-based cut paper, collage, and comics artist whose work explores the transformative capacities of found and handmade papers. Her cut paper comic “Sea” was recognized by Cartoonists Northwest as 2015’s “best comic book” and a selection of her poetry comics, collectively titled In Between (which includes the image above), is available from Pleiades Press. Mahato is Associate Curator of Public and Youth Programs at the Henry Art Gallery and serves on the board for the arts organization Short Run Seattle.

If you appreciate great writing like this, please consider becoming a supporting reader of Cascadia Magazine. To make a contribution at any level you’re comfortable with, please visit our donate page.