An Indigenous chief occupies an island and

triggers a war over British Columbia’s salmon farms

.

It’s May 6, 2018 and First Nations people from the village of Alert Bay British Columbia are intent on mounting a show of defiance against Marine Harvest —the largest salmon farm corporation in the world.

“Ha-yuhhhh!” bellows hereditary Chief Ernest Alfred in his Kwak’wala language with arms spread wide. The flamboyant and boyish-looking 36-year-old school teacher is standing on the lead boat, yelling a traditional salmon song at the corporation’s floating office.

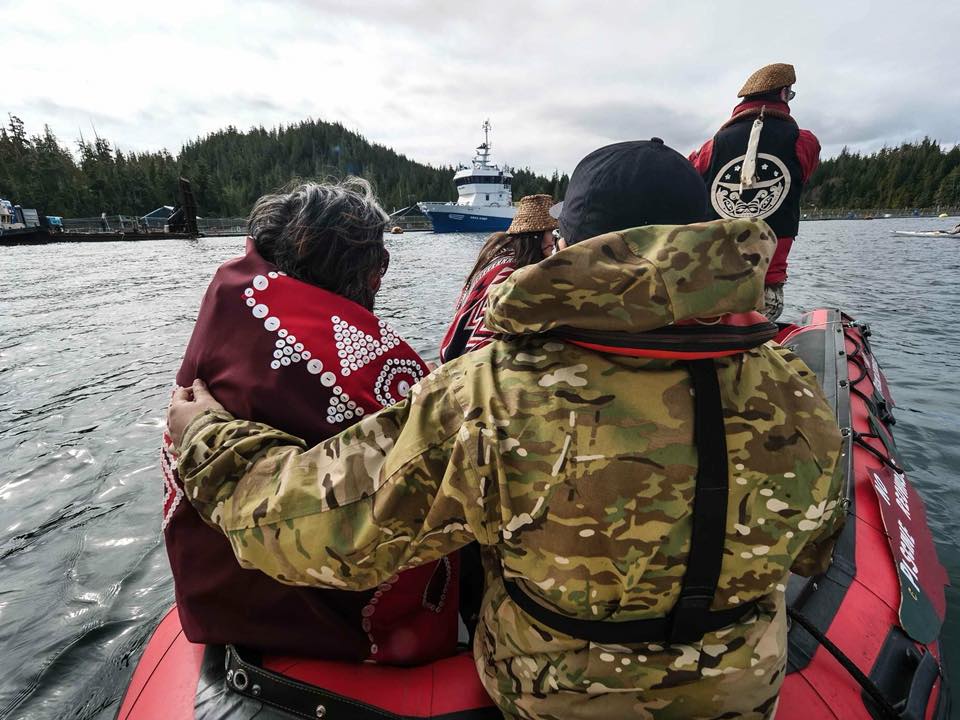

Chiefs, elders, and locals float behind Alfred in full regalia. Women are wrapped in navy and red blankets with ancient crests, and children hold signs: “Stop Open Net Fish Farms” and “Stop the Piscine Reovirus.”

The flotilla of vessels is a prelude to an Indigenous legal war seeking to prohibit the $1.5-billion open-net Atlantic fish salmon farms from Canada’s West Coast. First Nations fear the farms spread a virus deadly to wild salmon, and their efforts have been buoyed by Washington state’s recent legislation phasing out open-net farms by 2025.

The aquaculture crews that toss feed to the Swanson Island farm’s “Atlantics” retreat indoors and shut the blinds. The company is used to Indigenous acrimony. Twelve of Marine Harvest’s 55 facilities on this coast have been hit with raucous protests in recent months.

Alfred reads into his megaphone. It’s a response from the hereditary chiefs of the ‘Namgis and ‘Mamalilikala First Nations to a recent eviction letter ordering Alfred to leave the company’s cottage 200 yards away. He’s been occupying the cabin in plain view of Marine Harvest for the better part of a year.

“We cannot believe you had the audacity to write such [an eviction] letter!” reads Alfred. “We’d like to remind you that at no time did we give you the authority to make such demands regarding our traditional lands and territories. In fact, there was no consent given to you to be on our territory to begin with!”

As the boats draw closer, the frenzied splashing of one million maturing Atlantic salmon, with dozens jumping up every second, grow louder. Each will gain 11 pounds before a fall slaughter that packages them for supermarkets worldwide. By one estimate close to three quarters of the salmon on American dinner plates is farmed fish, harvested in remote spots like this one in British Columbia.

But the local tribes believe—backed up by recent federal science and personal observations—that the farms are harming wild salmon with lice, pollution, and a nasty virus. Salmon is a keystone species that feeds the entire Cascadia ecosystem —from whales and seals to bears and humans.

And while a recent federal study shows that the entire Pacific Ocean’s supply of wild pink, chum, and sockeye for the last 90 years “are more abundant” than ever, the local situation on BC’s coast is dire in the majority of audited areas. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans’ salmon outlook for 2018 shows that 68 percent of BC’s salmon spawning grounds (where there is sufficient data) are expected “to be of some conservation concern” or are of “mixed outlook.”

Even Marine Harvest suggests that wild salmon are no longer a viable option for feeding a global population set to add two billion more people by 2050. The company is fond of telling investors that 90 per cent of the world’s wild fisheries are already “fully exploited or overfished” and that moving food production to the ocean is a practical solution for a hungry planet.

The company recently won a court order barring Alfred from boarding its farm, and another is imminent seeking to block further boardings by him, biologist and fish-farm critic Alexandra Morton, and “John and Jane Joe.” Marine Harvest says it expects to be hit hard with protests this summer by the U.S.-based Sea Shepherd Conservation Society.

To avoid arrest, Alfred is careful to tiptoe on the edge of his boat, and not step off. But the other hereditary chiefs do and knock on the window. Several minutes pass, and they duct tape their letter to the door. Proud photos are snapped. An RCMP boat arrives later, but does not appear to investigate charges.

“There was a lot of peeking through the curtains,” says Alfred, moments later, chest beating. “I’ve never seen those curtains closed by the way — ever. The staff were there and they were probably told to not respond.”

“I think that the writing is on the wall for this company to just leave now. Count their losses and move on, and go somewhere where they are welcome.”

“The 30-year reign that the Norwegians have had in our territory is over.”

Marine Harvest’s Canadian public affairs executive Jeremy Dunn says the “activists were looking to intimidate our staff” when they circled the Swanson Island farm, and some of its employees are on stress leave. “It’s very unsettling and challenging for our staff who are farmers who have a primary responsibility to care for their fish to deal with this,” said Dunn.

“I fully respect the right of Canadians to protest any activity of an industry they feel they’d like to protest. What becomes challenging is when it’s interfering with our employees’ safe workspace. And that’s what unfortunately has been happening on a number of our operations,” he added.

Above: Members of the ‘Namgis First Nation post a response to Chief Alfred’s eviction on the door of a Marine Harvest office. The chief occupied a cabin on remote Swanson Island for 284 days to draw attention to Indigenous efforts to ban open-net fish farms. Photo by Jon Carroll.

.

The Swanson Occupation

On September 9, 2017, Alfred took control of Marine Harvest’s work cottage on tiny, remote Swanson Island —home to one bear, one dog, and himself. It was the start of what came to be known as the “Swanson Occupation.”

Inside the cabin are a scattering of laptops, mariner charts, an old iron fireplace and months of photos from well-wishers on the walls. Solar panels keep the wi-fi and coffee pot powered. There’s a sky-lit outhouse with a bag of wood chips to cover one’s poop. Marine Harvest says in court filings its building is “not suitable for long-term habitation” —something that gives Alfred a smirk, since he says he’s lived here quite comfortably.

Aside from the occasional arrival of journalists, film-makers, and environmentalists, Alfred has sustained this odyssey of discontent mostly alone—although lately, his auntie has joined him too. Living in solitude among these peaceful islands, where whale tails often splash might seem idyllic, but he admits, “It sucks, to be honest with you.”

Alfred has great highs, and great lows, and they are always on display. Radio chirps from the company’s CB are enough to make him grimace. He smokes constantly and keeps an ear on the fish farm’s radio chatter, and an eye on the crews through a monocular scope. He has nicknames for each Marine Harvest employee, and he has renamed the farm’s supply ship —the “Orca Chief”—to the “Orca Thief.”

By living this way, watching and recording the farm’s activities, from the company’s own cottage, Alfred is testing the legal limit of his right to protest. Luckily for him, his lawyer has a clever argument. Marine Harvest’s cottage sits atop provincial land, but with a park licence that expired in December. So Alfred and his auntie are essentially squatting on Crown land, a BC court was told.

In the early days of the occupation, Alfred says Marine Harvest’s then public affairs officer invited him to climb aboard the floating farm to observe the fall harvest. Alfred shot lots of video showing hundreds of flip-flopping, bloody salmon sliding down industrial chutes getting punctured to death. Other shots, collected by activists, zoom in on what he believes are sickly fish. Some have bulbous growths. Others are crooked and swim zig-zag. Among Alfred’s favourites: the ”Terminator fish.”

“We named it because of that movie with Arnold Schwarzenegger where he had his face blown off and it was just his eyeball there,” he says with a smile. While making no claim the fish is a cyborg from the future, Alfred is convinced the farmed fish are deadly to wild salmon. And federal scientists tend to agree.

The Department of Fisheries and Oceans says between 60 and 80 percent of the West Coast farms’ Atlantic fish are infected with piscine reovirus, which originates in the North Atlantic and is brought to BC waters via fish farms. A new DFO study in May found the virus causes heart and skeletal muscle inflammation in farmed Atlantic salmon, and jaundice and anemia in farmed Chinooks. Worse, “when the red blood cells rupture, they release massive amount of virus,” said the study’s co-author, genomics fish scientist Kristi Miller-Saunders.

The BC Fish Farmers Association called the science “theoretical,” since the study did not show examples of diseased wild fish. “While the virus in question is common, fish health issues on the farm are rare. The fish fare generally healthy. So the presence of these viruses does not equate to the presence of disease,” said spokesperson Shawn Hall.

Miller-Saunders says that’s because the infected wild salmon don’t survive long enough to get full diseases. They slow down and “get eaten by a predator, and they’re gone.“

Alfred points to what he sees in the water —a lot less salmon than there used to be. “These rivers, just behind me here —these rivers have sustained our people for thousands of years. We’re watching it go down, like seriously. We’re watching all of the fish disappear.”

Keeping a video diary

So to vent his frustration, nearly every week Alfred records a video monologue with his iPhone and posts it to Facebook. They have a familiar start — “It’s day 202 of the Swanson Occupation,” and he then proceeds to update viewers on his lawsuits and recent altercations with police or the company.

.

Marine Harvest is more explicit—it says in court filings that Alfred and other activists are bent on “destroying” its business, “harassing and making antagonistic statements” to employees, and “frequently photographing and recording Marine Harvest employees as they attempt to perform their duties.”

Greg McDade, a lawyer for long-time fish farm critic Alexandra Morton, says illegal protesting is in the eye of the beholder.

“If you’re the First Nations, and you watch [the fish farm industry] in effect pouring poison into water that are killing your wild salmon, I think your perception of whether those people are innocent and lawful occupants can be understood.”

Alfred insists his activities, while loud, have always been respectful. “We’ve not harassed those workers, and we plan to challenge that in court.

“They’re trying to eject us from our own land. We were not interfering with any of their operations. We never really have. When they wanted to harvest the fish from the site at Swanson Island and asked us to leave, we cooperated. We got up and we left.”

But facing these legal woes, and pressing the government for change, day after day, away from his job and family is wearing him and his loved ones down. “The toll —it’s not just me personally,” he says. “Our families have been negatively impacted, our relationships have become really strained.”

“My relatives keeps reminding me: ‘say we, us, and our’ more — not just ‘I.’”

When asked to show some of his fish farm video clips one evening, Alfred gets lost in them — clicking through each one, never letting the videos finish. He laughs at the good memories, feels sadness from others. Before long, he snaps the laptop closed and walks away.

Above: Aerial view of the Swanson Island cottage. At the end of the standoff, the British Columbia government announced in June that it would require future permits for commercial fish farms to meet First Nations approval.

.

The historical roots of discontent

The roots of Aboriginal discontent go deep into Pacific Northwest history. Chief Alfred sits on the Swanson Island dock to describe some of that story.

For thousands of years, the ‘Namgis had lived off the abundance of salmon, and adorned their clothing (as they still do today) with shellfish, furs, and distant treasures obtained from trade, he says. Then his people’s lives changed forever in the late 18th century with the arrival of disease and a mysterious foreign sloop with tall sails.

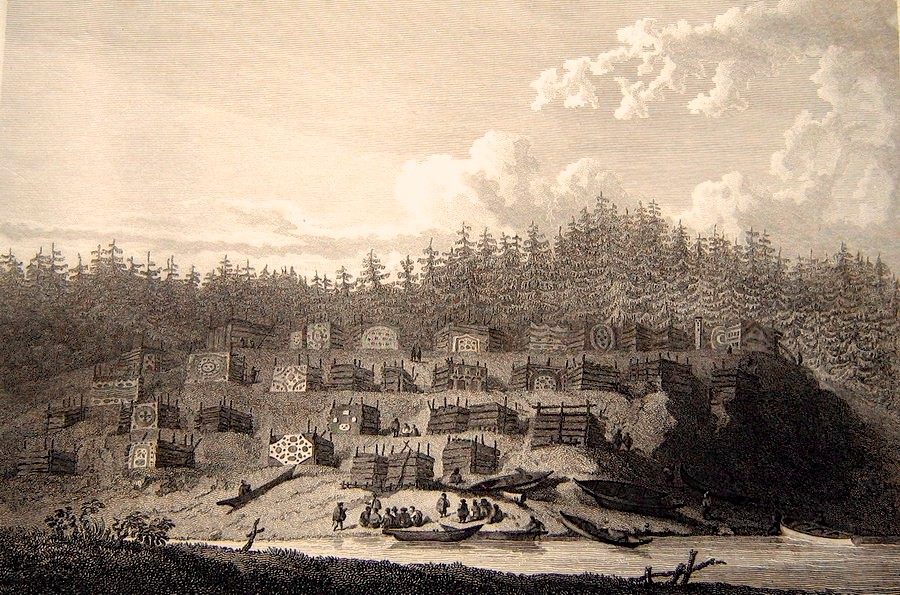

In 1792, Captain Vancouver of the HMS Discovery, who had also charted Hawaii and Australia, sailed into Alfred’s ancestors’ ‘Namgis village waters near present-day Port McNeil. The explorer was one of the first Europeans to make contact with his tribe. In the present day city of Vancouver, a statue at City Hall shows the captain pointing heroically.

“There was a crew member on his ship who drew a picture of the village that was at the mouth of the river, called Xwa̱lkw,” says Alfred. “That’s where our people lived.”

“We should’ve killed you white people right then and there,” he adds with dark jest. (Alfred’s auntie Tsastilqualus says Alfred’s jokes are an example of native peoples’ way of coping with past traumas.)

What the Royal Navy saw 226 years ago was rather apocalyptic. The captain’s macabre observations about this “delightful” and “thinly populated” country were indicative of an unfolding tragedy: a deadly smallpox outbreak introduced by Europeans had been sweeping the West Coast for years and left no Indigenous village unaffected.

“The skull, limbs, ribs and backbones, or some other vestiges of the human body, were found in many places, promiscuously scattered about the beach in great numbers,” wrote the captain.

It’s now understood that farming civilizations spread smallpox to the New World where Indigenous peoples lacked immunity. A cough, a handshake, or an infected blanket would bring mass death and misery.

As Canada was later constituted in 1867, the outlook for coastal native peoples did not fare much better. From potlatch bans to residential schools outside forces continued to subjugate. And much like African Americans, Canada’s Aboriginals didn’t have full, guaranteed voting rights until the 1960s.

But in 1982, not long after Alfred was born, Canada’s native peoples would earn a legal bonanza. A new Constitution enshrined Aboriginal rights that enabled them to claim title ownership of their lands. Words like “decolonization” became popularized, and Canada’s misnamed “Indians” became “First Nations.”

This independence would fuel the “Oka Crisis” of 1990 when Quebec Mohawks defied Ottawa and its soldiers in an armed standoff over a golf course development. “‘It was the Idle No More’ movement of the time,” says Alfred, who stole the moment to be on national television at the age of eight.

The TV broadcast, he says, showed a map of Canada that then zoomed into his village of Alert Bay, and then to himself as part of cross-country Indigenous reactions. He still delights in this kind of media attention. “Mychaylo and I are having a popularity contest,” Alfred jokes to others in my presence. “He thinks he’s been on TV more times than me.” (As a former TV reporter of nearly a decade, I’ve been on TV more than 1,000 times, but never mind.)

Alfred is fond of telling reporters, and anyone who’ll listen, about the inter-generational gripes his family has had over the country’s management of wild fish by the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

“My Dad taught me, ‘DFO fucked up’ when I was a little kid, and I still remember. At that time, you could still come up here into the Broughton… and load your seine boat with pink salmon. It just goes to show how long the Department of Fisheries and Oceans has been ill-equipped to manage the resources of the West Coast.”

“I want them fired.”

A surreal confrontation

Ironically, one of the more unusual confrontations at the Swanson Island cottage happened when Alfred was away. On March 7, 2018, two heavyset security guards in neon vests arrived without notice to deliver an eviction letter to him.

Instead they found his 23-year-old niece, Karissa Glendale, who pulled a Rosa-Parks-like moment of defiance. A video of the moment has now gone viral.

“I am a licensed security guard. You need to move—now,” said one of the men.

“You’re not a security guard of this place,” replied Glensdale.

“Yes I am.”

“No you’re not.”

Marine Harvest claims in court filings that the young woman “physically blocked” these large men. And that she did, but by standing in their way as they both tried to pick her up.

“This is my territory,” she said.

“This is not your building,” said the guard.

“My territory. ON – MY – TERRITORY.”

The men asked her to turn off the video recording. Glendale refused. “You just tried to push me around. Two men, tried to push a woman around.”

“It’s our right, it’s our territory,” responds the guard. “I’m a Canadian. I’m a ninth generation Canadian. My grandfather came here in the 1800s, from Nova Scotia.”

“Canada is only 150 years old. We’ve been here for thousands and thousands and thousands of years.”.

“Oh yeah? My family’s been on the earth for thousand and thousands and thousands of years.”

“This is unceded territory.”

“Bullshit,” says the guard.

Above: Atlantic salmon in a Marine Harvest pen. Illness is common in farmed fish, which live in cramped, crowded conditions. Some studies suggest that piscine reovirus and sea lice are transferred to wild salmon. Photo by Tavish Campbell.

.

Turning the tide

By May, after nine months of occupying Marine Harvest’s cottage, a judge ordered Chief Alfred to vacate it. Alfred posted to Facebook a video of a native flag in the sky as he boated away. “Our flags and heads are held high. We have nothing to be ashamed of,” he wrote.

Alfred then focused on BC premier John Horgan, and a June 20 deadline in which twenty contentious fish farm licences were up for renewal. Alfred urged his supporters to call their local legislators. Renewing the licences, he said, would be “political suicide.” The NDP is only in power with a razor-thin one-seat advantage, propped up by the Green Party.

A few days before the deadline, premier Horgan held a press conference in Victoria to announce a new direction for salmon policy.

“I am just delighted to be here to announce a wild salmon strategy for British Columbia,” Horgan began. A Wild Salmon Advisory Council was promised, tasked with preparing an “options” paper about the future of the industry. Further announcements about the licences would be made in a few days.

That didn’t sit well with Alfred’s auntie who was hoping for an outright cancellation of the farm leases.

“You reneged on your promises!” yelled Tsastilqualus Ambers Umbas. “We don’t have time. Our salmon are dying!”

“I will certainly take that into consideration,” said the premier.

“You’re not taking anything into consideration! You’re putting up another road block!”

“I don’t agree with you.”

“You sold us out! It’s the same with Trudeau!”

“If that’s your view, you’re welcome to put your name on a ballot anytime soon,” said Horgan.

Umbas then told reporters, “I want [the fish farms] out of our waters completely. We don’t have time to waste. Our salmon is one of the most important things to us as Indigenous people. It’s our culture, it’s in our songs and dances – everything.”

Finally, the June 20 deadline arrived, and at a press conference, BC’s agriculture minister Lana Popham tapped her microphone nervously and took a deep breath. “When we first became government, we stated that fish farm policy would be done differently,” she began. “Today, I’m announcing a new approach…”

Popham went on to announce that, effective in June 2022 —in four years — the province will only grant companies fish farm tenures if they meet two conditions: one, that they satisfy Ottawa that there is no harm to wild salmon; and two, they have agreements with First Nations. The move will give the industry time to explore transitioning to land-based farms that have no impact on wild salmon.

But there was also a twist.

The most contentious fish farms in the Broughton Archipelago would only operate on a “month to month” licence while talks were underway with the three local First Nations. “I’m very proud of the historic nature of those talks and I will be reporting on them soon,” said Popham. She also clarified that “there is no veto” for First Nations. “This is a framework to reach agreements,” she insisted.

This prompted a sharp rebuke from the Dzawada’enuxw, which announced they were leaving the talks, and promised to step up its lawsuit to remove nine fish farms from its “Aboriginal Title” territorial waters.

But listening live to the minister’s announcement was Chief Alfred, who after 284 days since he first occupied Marine Harvest’s cottage, felt upbeat.

“I think it’s a really bold step in the right direction. I am hopeful.”

“They’ve issued not a renewal, but an extension of the tenure for the next month. So what we’re hoping, that in the next few days, we’ll hear a decision on at least a few of them. We’ve made it clear that some of the farms are particularly dangerous to certain river-runs of salmon.”

Right after the press conference, the minister called Chief Alfred — a sign, he says, that the Swanson Occupation had a “major effect.”

“We are in the news, and we have ministers calling us. Even though we pay personally… and suffered a great deal, I still think we should walk away from this with a lot of pride and a lot of dignity.”

“They need to understand that —with everything that our people have gone through —this, we can handle. We’ve been through worse.”

Cascadia Magazine is dedicated to publishing quality journalism about issues that matter. We depend on the generous financial contributions of readers like you to pay our writers and photographers a fair rate for their work. To support these efforts, please visit our donate page.