A poet’s account of being arrested and sentenced for protesting the Trans Mountain pipeline

I don’t want to be depressed. I want to be productive during my conditional sentence. But solastalgia* seems the only rational response to the rapid depletion of our natural world. My body weighs heavy – a stress-induced arthritis flare-up – my hands and feet numb. I sleep twelve hours a day and cry for my friends in prison. I cry for myself. I drag myself to my computer because I have to speak for them, since they are temporarily lost to the outside world. I am grateful for Internet. In the intimacy of dark, wet days under desk lamplight, I feel my friends around me.

Here on the coast of British Columbia, large-scale destruction is mirrored in the rural area in which I live. This past spring, a sudden razed acre behind our home put me in a state of despair for weeks, sitting at the edge of our property in tears, talking to the one ancient maple left behind. Her children and grandchildren piled alongside the new road that will lead up to a future house. It was the way the light had changed that brought me to my knees. The way it had cooked both earth and Grandmother Maple’s moss to a crisp. The chainsaws had frightened all the squirrels away; we found a displaced baby sparrow in the grass.

I think I am the only one in my neighbourhood who thinks it odd to spend what I consider a ridiculous amount of money to “own” a piece of land with some reconfigured trees shaping the corners of a box to hold us and our possessions. The only way I can reconcile this is to tell myself we have not paid to own this land, but we have paid to keep it safe.

On this shy acre there will be no lumber mill. The bees will have safe passage, be coaxed to proliferate the flowers. The deer will drink from our stream; the old growth trees will grow their moss. I will dig my hands in its soil and plant seeds, and when the clouds pass over, they will breathe and sigh in relief. There will be no road but the leaf highway of stones. There will be no factory. After the apocalypse, you can bring your tents and live off the fig, apple, plum, pear trees. The wind will find bark and branch and needles to sing through.

We’ll watch end-of-summer cubs play on the lawn. I am the momma bear, too.

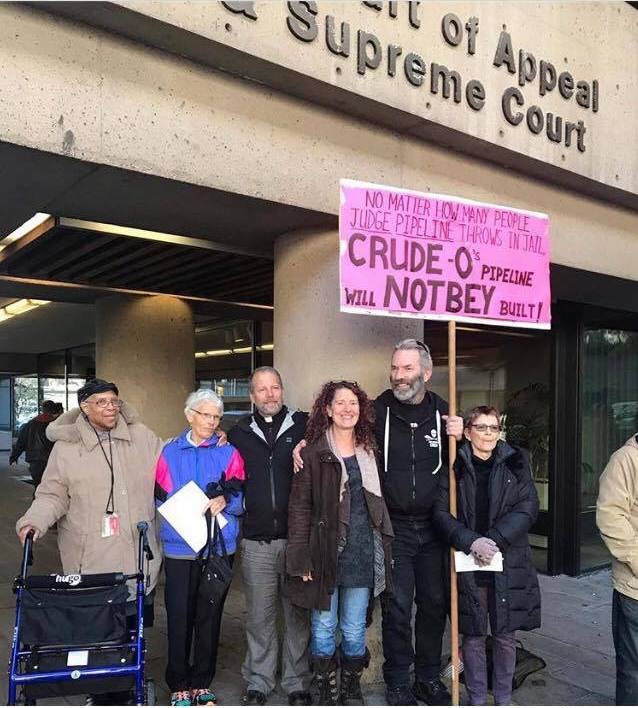

I was among five people (at 50-years-old, the youngest) arrested on May 18th, 2018 on Burnaby Mountain in British Columbia. We had crossed the court-ordered injunction line around the Kinder Morgan tank farm, blocking a truck from leaving the facility. We knew what we were doing. Our first time in court, we told the judge we took full responsibility for our actions. That day, the Crown Attorney announced they were going to start increasing sentences.

We weren’t the first to be arrested; almost two hundred had been arrested before us in solidarity with First Nations to save our waters, our endangered orcas, our air, our trees. United in our grief, for this planet, and for what will be lost to its children.

On our trial date, I sit in the defendant’s box next to the Reverend Dr. Victoria Marie, a 73-year-old African Canadian ordained priest, while Crown Attorneys lay out arguments for her sentencing. A warm, grounding presence always dressed in layers of lavender and blue, Reverend Vikki waits patiently in the seat of her rolling walker. She’s still healing from jaw reconstruction due to a cancerous growth, and is being treated for another malignant tumour. I met her when she sat down next to me at the gates of the Kinder Morgan tank farm the day we were arrested. She told a reporter, “What do I have to lose? I’m dying. I’m going to do whatever I can before I leave this earth.”

I listen to the Crown Attorney tell the judge we must be punished for disrespecting the Rule of Law; if not, the country would descend into anarchy. I turn to my left, to Jo – a former social worker and the 66-year-old Louise to my Thelma – who I also met on the mountain. We mouth to each other: anarchy? Titters emerge from the packed gallery behind us. The Crown refers to our acts as “sinister.” More tittering.

Next to Jo sits Judith (a retired counsellor) and then Ron (an ordained deacon in the Anglican Church with an earth justice ministry focus). We had not known each other before our arrest, but had become each other’s source of strength and connection.

I look back and forth between Rev. Vikki and the Crown Attorney spelling out the need for increased sentences to deter our unlawful behaviour and think: What the fuck are we even doing here? The planet is on a crash course with worldwide environmental catastrophe, and you’re discussing why a 73-year-old priest, dying of cancer, should be sentenced to 250 hours of community service for sitting peacefully in front of an oil tank farm in defence of all we hold dear? It’s all too surreal. I dissociate from the scene, as if I’m watching from beyond us, from a future that looks back on this court’s proceedings wondering how humans could have been so stupid.

When it’s my turn, I look the judge in the eyes as my lawyer told me to. I’m calm. Years of being a performance poet support my voice. I am surprised that he also looks me in the eyes as I read. I am surprised to see that he is listening.

We’re allowed to make statements previous to sentencing, as have the arrestees before us. Nothing that’s been read by Indigenous people, health care practitioners, scientists, social workers, educators, grandmothers, politicians, or faith leaders has swayed the judge — we needed to be punished, otherwise, you know, anarchy —But we give it our best shot. Rev. Vikki goes first. After her intelligent, well-researched, heart-felt statement (you can read it here), the gallery erupts into applause. Judge Affleck pounds his gavel and says we are not allowed editorial outbursts, and the next time it happens he will clear the gallery. He says this every time. We always get one good cheer in.

Judge Affleck rules for a reduced 120 hours—5 hours of community service every week for six months, which, of course, Rev. Vikki’s already arranged with a charity—since she has to navigate through post-op doctor visits and medical treatments. As she accepts her sentence, she corrects him when he calls her Ms. Marie.

“It’s Reverend Doctor Victoria Marie,” she says calmly. Even the RCMP security guards have to grin.

When it’s my turn, I look the judge in the eyes as my lawyer told me to. I’m calm. Years of being a performance poet support my voice. I am surprised that he also looks me in the eyes as I read. I am surprised to see that he is listening. I make it to the end before sadness chokes my words:

Judge Affleck, I don’t know what keeps you up at night. I don’t know what injustices break your heart. I don’t know who and what you cherish or would fight for when global climate destabilization changes our lives forever. I don’t know what it would take for you to pick up one of our signs and march with us. But I do know this, if the day comes when your heart reaches its own tipping point and you cannot watch what is happening to our world any longer, and you decide to speak up, you will not be alone.

Before he announces his decision, the judge tells us we are accomplished, articulate, inspiring people; but our pleas have nothing to do with our crime of breaking his injunction. In his world, climate change, Indigenous rights, health hazards, and the extinction of species are separate issues from our disrespect of the law.

No one is surprised; we’ve been at this for months.

But he was listening to us. I know he was, and I picture a pile of hardened sand around his heart, and each arrestee statement a drop of water slowly dissolving the way back to it.

The remaining four of us arrested that day face seven days in jail. Our lawyer argues for fourteen days of house arrest instead. The judge says he’ll take three days to think about it, and we’re dismissed into the sunshine. Jo and I walk in a daze down Robson Street among commuters and shoppers. I stop in the middle of the sidewalk, surrounded by commerce and consumption and assimilation and disconnection.

“Jo,” I say to my co-conspirator, “none of these people know what’s going on. They have no idea what’s been happening in that courtroom.”

“No,” she agrees, “they don’t.”

I’m sad and angry all at once. What has engulfed our lives hasn’t woken anything in these people. All these sleepwalkers, who a few months ago had been breathing and exclaiming about the smoke from hundreds of forest fires across B.C., what will it take to get their attention? To get them to act?

I prepare to go to jail like I prepare for everything else. I do my research. I look up Alouette Women’s Correctional Facility in Maple Ridge. Find someone to pick us up and keep our cell phones until we’re released, check the ferry and transit schedule, find a place to stay in Vancouver the night before incarceration, write my ride’s and my lawyer’s numbers on my arm in sharpie, take out all my piercings.

I ask questions. Can I take anything in with me? Do I need a note from my doctor for my prescriptions? As a lactose intolerant pescatarian celiac, what will I eat? And, most importantly, will I have access to pen and paper? I am determined to document this experience even if I have to do so with ketchup on napkins.

We stay in touch, those of us arrested together, and pass along news, advice, and encouragement. It’s nerve-wracking trying to guess what the judge will decide, but Jo and I assume we’ll all get the same deal. Jo’s confident about the house arrest. Everyone else agrees how well our lawyer argued for it. I’m not so sure.

On the day of sentencing, everything is drawn-out in court-time tediousness. Each action is read out in legalese. I’m exhausted; I just want this over with. Ron and I are first. I stand with butterflies in my stomach, clutching my plastic bag full of medications and doctors’ notes. Judge Affleck rules that due to my rheumatoid arthritis and celiac disease, incarceration would be cruel, and sentences me to 7 days house arrest and 150 hours community service on a year’s probation.

On the day of sentencing, everything is drawn-out in court-time tediousness. Each action is read out in legalese. I’m exhausted; I just want this over with. Ron and I are first. I stand with butterflies in my stomach, clutching my plastic bag full of medications and doctors’ notes. Judge Affleck rules that due to my rheumatoid arthritis and celiac disease, incarceration would be cruel, and sentences me to 7 days house arrest and 150 hours community service on a year’s probation.

I’m numb as I sit, and Ron stands. Jo leans forward and frowns. She knows I’m upset about the community service. A minute later Ron is sentenced to an intermittent 7 days in jail. Then Jo and Judith get sentenced to 7 days in prison and are taken immediately into custody. I panic as they are led away. It has all happened so fast after months of court dates, conversations, and reading legal information in anticipation of the judge’s decision. I don’t want to be separated from them. We are in this together.

Ron sits with me for almost three hours while I wait for my paperwork. His intermittent sentence will be served in his hometown. I feel guilty when our lawyer stops by. He’s happy about the house arrest. I was the first protest arrestee to receive a conditional sentence. It sets precedence for the remaining cases, he says, in particular for his 85-year-old client faced with fourteen days in prison.

It’s not the house arrest that bothers me; it’s all the rest of it. I’m tired. Devastated that it isn’t going to be over, so I can get back to the larger issue of our impending extinction. I’ll have to report to a probation officer, get my community service approved, and find time within everything else I do, to get it all done.

“My whole life is community service,” I complain to Ron. “What we did on the mountain was community service.”

I feel ungrateful. I feel privileged. I feel overwhelmed.

My friends are in prison, and I am not. I have trouble getting anything done. I wander the house in a daze, alternating through grief, guilt, anger—collapsing from the anxiety of the previous month’s anticipation of our court appearance and knowing this is only the beginning of our fight. I cannot rebury my head, nor can I ignore what has become for me a desperate calling. It felt, at times, that Jo and I were gripping each other to keep from falling into too dark of a place. We know this is only one action in a future of actions as we head toward an uncertain future.

We had decided no matter what we pleaded, and no matter what sentence we argued for, we would respect each other’s decisions. Everyone needed to make the right choice for themselves. Only, this wasn’t the sentence I wanted. Odd as it sounds, I would have preferred go to jail. For one thing, with jail it’s over and done with. More importantly, we would have been together, welcoming all the other women as they were sentenced. The connection had become that important to me. It kept me grounded and sane.

As I made my way home, tired and alone, I hoped that my probation officer would be kind.

I am no hero. My fellow protestors and I agree: our courage is not extraordinary. We were simply so deep in our despair we were overcome with the need to do something. . . . Crossing the injunction line was the easiest thing to do at the time, because not crossing, not acting, not demanding was more frightening.

The next morning, my body gives out, the sciatica kicks in, my fingers and toes swell up, and I start to feel a little bit grateful for not being behind bars. I drag myself to my computer. With my friends in prison I feel the need to be their voice on the outside. The beauty of the Internet is that I can share their experience through my tears and find support and solace in a community of like-minded people.

I write about what’s happening with the protestors. I promote Extinction Rebellion’s activities. I eat a lot of 5-minute mug cakes, take baths, read, and work on some poems. I think of my friends. The days blend into each other. Nothing ever seems like enough. I forgive myself for only being able to do so much.

Oftentimes, the issues we got arrested for in the first place seem insurmountable. Sometimes, I cry myself awake in the morning because I love the world so much it hurts. And I cry because of my privilege. I was arrested gently, I had a lawyer, a home to be released into, a rallying community. Friends. I live in a breath-taking place fairly untouched by the greater ravages of climate change.

The stories shared once protesters are released from prison tell of the women they left behind at Alouette. Of not-so-gentle arrests and not-so-gentle lives. I ache when others don’t understand that those of us with privilege need to stand beside those whose voices go unheard or who risk so much more for speaking up. We need to understand the consequences of our actions—and inactions—on others. It is empathy within our anger that will save us.

So many issues fight for our attention. Since the election of Trump, those causes have multiplied. Since the election of Trump, I have felt bombarded by new issues daily. It paralyzed me for a while. Being a children’s author felt like a luxurious waste of time. Another book tour seemed selfish. How could I go on with my previous life while the whole world was crying for help? I decided I had to do something. I can’t do everything, but I have to do something.

And in the end, if we don’t save ourselves, none of those other causes will matter.

I can’t do everything, but I have to do something.

I could not ignore that inner voice. So, I went to the “front lines” and was humbled by the people I met who have dedicated their lives to the resistance. Humbled by the risks people take who have bigger targets on their back than I do. If I cross the injunction line, what risk am I taking? A middle class, middle-aged white woman with no immediate threat, yet, of losing her livelihood, her food supply, her home. When I am approached by a police officer, my first thought is never, I’m going to die.

I am no hero. My fellow protestors and I agree: our courage is not extraordinary. We were simply so deep in our despair we were overcome with the need to do something. An opportunity presented itself and we took it. Crossing the injunction line was the easiest thing to do at the time, because not crossing, not acting, not demanding was more frightening. What happens if we don’t cross the lines? What are the consequences of not demanding immediate change? I am more frightened when wandering among downtown commuters and shoppers stuck in an automated cycle of work, spend, consume, distract.

I am afraid I may start shouting at traffic and pedestrians if I don’t channel my emotions.

Jo shows up at my house on day five and we latch onto each other tightly in the doorway. She and Judith were let out for “good behaviour,” which makes us laugh. She tells me her whole story, from the minute they were taken away to when she was released. Five days with the women of that prison, and she is so worried for them, especially for the time when they are released with no more support, skills training, or addiction counselling than they had before.

I tell Jo that her life will now always be divided between, Well, before I got arrested… and after I got out of prison… We laugh some more. Sometimes people think activists have no sense of humour. I’d say it’s vital. We also sing and play and find joy together. Jo and I agree there is no going back to the way we used to live in the world. No way to stop showing up. But, we have to stay balanced. I call it “tag team activism” when one of us decides we have to check out.

It’s a pattern in my life: I burn myself out time and time again, only to go dark, recuperate, and start all over again. Sometimes my disease shuts me down and forces me to take a break. Jo tells me to look at my house arrest as simply a forced recuperation period.

Things seem doable again after she leaves. I take stock of my blessings. I have Jo. I have a support system. And my probation officer has turned out to be pretty cool. He tells me I don’t have to do any more than I’m already doing. I can use my time organizing and producing educational and community events around climate change towards my 150-hour sentence.

“Irony is the best revenge,” I joke to my friends.

At a protest sign-making party I’ve organized, I tell people I am nobody. Not in that humbled sense, although being among protestors is itself a humbling experience: meeting those who have for decades been activists and recidivists, meeting those who have dedicated their entire lives to calling out injustices, and walking with those for whom injustice is a daily experience. I am a nobody in the sense that no one elected me or hired me or even asked me to stand up or organize or speak. I’m nobody in the scheme of all of this, but when I stand up with others, we are somebody.

I tell my friends, “That somebody you’re hoping will step up and do something, that’s you. That’s me. That’s us.”

We are in this together, hurtling towards an uninhabitable planet, and not acting fast enough. We can’t all be full-time activists. We can’t all be the Light Workers of the world. But activists and Light Workers burn out.

I believe we, the privileged and the people who have been called to do other things, need to be the activists’ support, their glue. We need to step up and stand with them. We do not have time to play small. We do not have time to wait to grow confidence behind our voices. We do not have time to wait and see what happens. We do not have time.

*existential distress brought on by environmental change

Long-time writer, educator, and spoken word artist Danika Dinsmore serves on the editorial staff of Reckoning, a literary journal of environmental justice, and on the board of directors of Cascadia Poetics LAB Society. She has turned to creative activism as a means of expression and creative expression as a means of activism. You can support her work at her Patreon page, Content for the Literary Tree Hugger.

If you appreciate great writing like this on issues that matter in the Pacific Northwest, please consider becoming a supporting reader of Cascadia Magazine. You can contribute at any level you’re comfortable with at our donate page.

And it you’re already a supporting reader of Cascadia Magazine, thank you!