.

Kristen Millares Young is no stranger to the writing and journalism community in the Seattle area. Her resumé is impressive: after earning a BA in History and Literature from Harvard and her MFA from University of Washington, she built a multifaceted career that includes investigative reporting (including as part of a team that won a Pulitzer and a Peabody for their work on the New York Times’ “Snow Fall: The Avalanche at Tunnel Creek”), creative nonfiction, and fiction. Her writing can be found all over many A-list publications, including this one. She is a writer-in-residence at Hugo House in Seattle, and also teaches writing at libraries in the area.

Subduction (Red Hen Press, 4/14) is her debut novel, but it’s clear from reading it that Young is already a master of the craft. This uniquely complex story follows Claudia, a Latinx anthropologist driven by academic and capitalist ambition and at the end of her rocky marriage. The book takes the reader to Neah Bay in the northwestern corner of Washington state—the land of the Makah people. Claudia attempts to salvage—or forge—a sense of self by immersing herself in a project to create a written record of Makah culture. She does this mainly by interviewing an elder named Maggie, who in addition to being a pillar of the community is also a hoarder and suffers from dementia. The return of Maggie’s son, Peter, for the first time since he fled as a teenager after his father’s death, coincides with Claudia’s arrival, and the meeting of the two has reverberations that ripple the earth around them.

Cascadia Magazine sat down with Young to talk about writing deeply complicated characters, how identity and place are intertwined, the problematic nature of memory, the need to preserve elders’ stories in this new pandemic era, and driving alone on logging roads.

Subduction is very much a book about the Pacific Northwest. What does living and working in this region mean to you as a journalist and a novelist? What was the spark for this particular story?

I went out to the Makah Nation for the first time in 2005. I had just come to the Pacific Northwest to work as a staff reporter for the Seattle Post Intelligencer, and I was on a road trip, to do a tour around the Olympic Peninsula. I like to just drive around and try to figure out where I am. I look at roads as veins into communities. The farther up a logging road I can drive, the happier I am, although I am sad that there are so many of them.

I used to have a Honda Element where you could put the seats up in the back, and then sleep in it. As a woman traveling alone, and ending up in random places, this was pretty handy. I drove out to Neah Bay, and I didn’t have any real idea about what I was going to find there. But just as you come into the territory, the Makah and Cultural Research Center is right there on the left as you drive in.

I knew that I had a five-hour drive to get back, and I knew that, the next day, I had to get up and go to work. I used to crush work as a reporter. That was my life. But I decided to stop, and I met this guy, Kirk Wachendorf, who I ended up interviewing later on for the Seattle PI about his work as a docent for the Makah Cultural and Research Center.

He started telling me about having to carry around an ID card in order to prove that he was Native and what an insult this was to the First Peoples, that they should be required to produce identification in this way. As a citizen of the United States, I of course have had to produce my passport in order to travel and my driver’s license in order to drive around. But I’ve never had to prove my race, or ethnicity, or affiliation, even though as a mixed white and Latina person, I’ve often been asked, “Why do you speak Spanish?” or, “What’s with your hair?” [I’ve been] questioned on elements of my presentation to try to ferret out origins, but not in an official way. The last place that I had been where people did have to produce documentation, had to have it with them all the time, was in Cuba where you can just walk around, and the police will just hassle you for your carnet—it’s like your card.

It invokes this involvement of the state that’s threatening, [and that’s] meant to prove something that you don’t want to lose. I became very intrigued by that idea of having to prove what you already are to people who were not what they are when they first came here.

On the way home, I pulled over along the strait, which is this captivating, winding, pinwheel, kaleidoscopic drive through all of these areas. I pulled over, and I just wrote one word: subduction. I put stars next to it, and I underlined it. And then I went home.

From that moment on, I felt this compulsion to return and try to learn more about these people who had preceded my arrival to this corner of the world by so many thousands of years. I had studied history and literature of Latin America as an undergraduate at Harvard. Through that, I read so many primary source documents about conquest that were provided by both the Conquistadors and the Indigenous people that they tortured.

So I had a meta-awareness of indigeneity and its importance, and the historical roles, and all of that. But it was when I came to the Pacific Northwest that I really began to appreciate how modern governing bodies, Indigenous tribal councils, and sovereign nations are all around us. And yet their importance and their presence in this ongoing story that is our country had not been impressed upon me in the same way. I felt that I had been badly educated because there is no historical process which is not ongoing. And so I wanted to learn what I could without mediation from textbooks or other sources, which had clearly been written to effect a record that was incomplete.

I want to talk about the idea of voyeurism, because Claudia ostensibly wants to create a record of Makah traditions and culture so that it’s not lost. But just by being there, she’s changing things. Can you talk a little bit about the idea of preserving a collective memory or a culture, and altering it in the preserving? Also, culture isn’t static, it’s dynamic. Where does that dynamism fit with the importance of tradition or memory?

Any person who has interviewed someone and then produced a record of that interview knows that there is a necessary winnowing that happens through the process of curation. It is not possible in most stories to include all of the record. Nowadays, you can hyperlink it or something if you want to. You have to decide what is going to stay in and what is going to be left out.

When Claudia is trying to make representations of her interactions with Makah people, she often tries to minimize evidence of her own duplicity, her own subjectivity, and she covers her tracks in a way that is dishonest. In [writing] that, I wanted to get into the problems of having interlocutors for any kind of information because you’re seeing that curation through the prism of that person’s subjectivity. That leaves a signature on what remains, whether or not that’s considered to be an official document like an ethnographic document or if it’s in the form of a fictional story.

In order to honestly depict the fraught possibilities, that had been evidenced by the long history of anthropological engagement with this and many other communities, the text itself [needed to] always be calling into question the process. Through Claudia, I draw attention to the inherent complications of curating any story from such a complex culture and about that complex culture’s interaction with another complex culture, which is the truth of American intersecting identities today.

Culture and imperialism aside, there is no monolithic American culture. It’s everything. And to try to winnow it down enough that people can see what’s at stake is something that I was interested in doing in this book.

You have to think your way through these characters. They don’t do and act right. [I wanted the reader to think], “What would I do? What should be done? What has been done? What does it mean?” To have the [characters’] mistakes occasion that kind of thinking was a risky choice that I made as an author in the hope that it would dislodge some of the recurrent thinking that sets in when people don’t deeply engage with a story, or when they’re not engaging with a certain culture. They think that they know what it is, but they don’t really know. The only way to come to know is to doubt and ask questions of yourself.

I was raised in a household, a Cuban household, that really values the elderly. This country, the U.S., does not value our elderly the way that we should. Urban culture does not value or center the elders the way that the Makahs, for example, do.

Memory plays a really important role in this book. Maggie, Peter’s mother and the Makah elder who Claudia connects with, is a hoarder and has dementia. She tries to preserve everything (personal and cultural) for her son, who in turn accuses her of never having been so devoted to their cultural rituals when he was younger. Can you talk about the role Maggie plays in the book, and about the role of memory in the story?

What Maggie is preserving in her body and in her home is a living culture. And any mind, any life, is messy. Anyone who has ever been a brooder knows that you could pop up a memory from 15 years ago from a social situation that no longer applies, and run through everything that happened as though you were trying to pan for gold. And why? Why, when you could say that it’s not part of the story, the most important story, or central narrative of your life?

But we all carry those kinds of memories. And most people’s homes, unless they’ve done the Marie Kondo method, are cluttered as a byproduct of living. Part of what I find interesting is what Claudia finds valuable about Maggie versus what she does not find valuable about Maggie. And it’s not as simple as it might seem because, of course, Claudia treats one of the stories that Maggie gives her with incredible discretion. She doesn’t tell Peter about what Maggie told her. I feel like that’s one of the more honorable moments that Claudia has. She knows this woman has the right to decide what she conveys to her son. But, for me, when looking at Maggie and Peter, what I find so interesting about their dynamic is that there is this shared trauma that they have tried so hard to contain in their life that it ended up shaping their life.

I think anyone who’s been in a family that harbors trauma knows the way that the untold story can basically trace the contours of the entire family. Even if no one is talking about that thing, it still ends up controlling and being the underlying current for all of the surface interactions. And that, to me, is very interesting, how the scar tissues can tug on the skin.

And Maggie is delightful, too, right? She’s funny, she’s smart. When she’s with it, she is way far ahead of everybody around her. And she has fought to keep it together long enough against strong prevailing winds to have this moment with her son. As embodied resilience, Maggie impresses me, even as she exhibits just as much human frailty as Claudia and Peter.

I was raised in a household, a Cuban household, that really values the elderly. This country, the U.S., does not value our elderly the way that we should. Urban culture does not value or center the elders the way that the Makahs, for example, do. What Maggie’s [dementia] presents is the urgency of our need to reorient our values to understand what they know before it passes from the Earth. It’s both the responsibility of that elder to take the time and invest in the process of preserving their knowledge, whether it’s in the form of oral storytelling or other kinds of storytelling. But you also need to have that person who’s willing to listen. Unfortunately, I think a lot of people have had this sense when their elders have passed, they wish they had spent a bit more time asking them about things.

And of course, we’re going to be feeling that so much as so many of our elderly and vulnerable people die, over these next couple of months. As a society, we are about to experience collective loss of knowledge and personhood. To me, this pandemic introduces urgency to the need to call your old people, talking about the way things are, or the way that they have been, the way they wanted them to be. Talk to them, listen to them.

What are you reading right now? Any local writers or artists you want to shout out?

I’m about to start reading a book called A History of My Brief Body, by Billy-Ray Belcourt. I read his work in Elissa [Washuta] and Theresa [Warburton]’s anthology, Shapes of Native Nonfiction. Then I was at Winter Institute, and I picked up a bunch of books in the hopes of finding the books that I wanted to review. I started reading it. It’s really f*cking good.

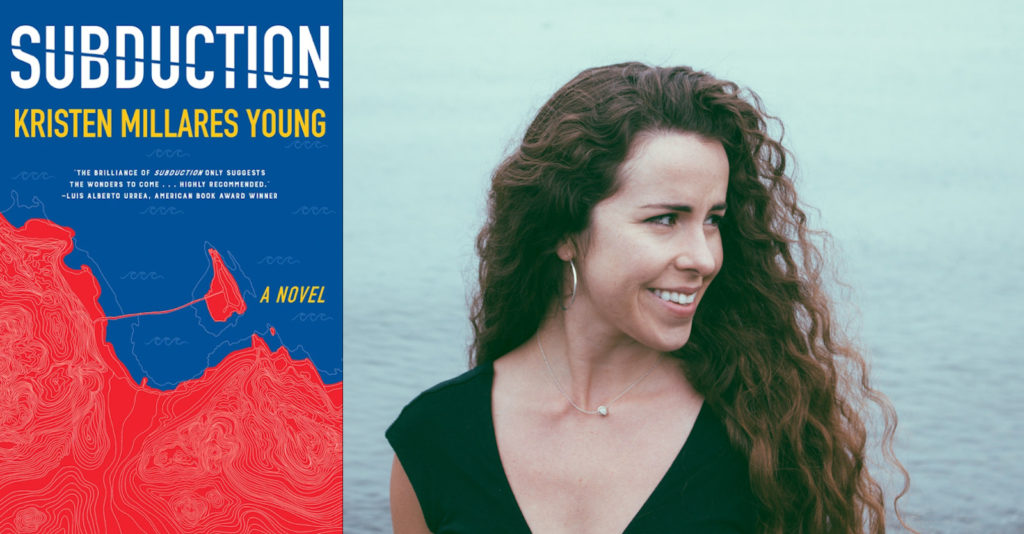

Photo of Kristen Millares Young by Natalie Shields, cover of Subduction courtesy of Red Hen Press.

Sarah Neilson is a freelance writer and book critic whose work appears in Electric Literature, LARB, LitHub, Buzzfeed, Rewire News, Seattle Times, and Bookforum among other outlets. She can be found on Twitter at @sarahmariewrote, Instagram at @readrunsea, and on her website, sarahneilsonwriter.com.

Kristen Millares Young is the author of the debut novel, Subduction, as well as being a prize-winning journalist and essayist whose work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Guardian and the New York Times, along with the anthologies Pie & Whiskey, a 2017 New York Times New & Notable Book, and Latina Outsiders: Remaking Latina Identity. The current Prose Writer-in-Residence at Hugo House, Kristen was the researcher for the New York Times team that produced “Snow Fall,” which won a Pulitzer Prize. She graduated from Harvard with a degree in history and literature, later earning her MFA from the University of Washington. Kristen serves as board chair of InvestigateWest, a nonprofit news studio she co-founded in Seattle, where she lives with her family.

.

If you appreciate interviews with Pacific Northwest authors like this, please become a supporting reader of Cascadia Magazine by making a contribution at our donate page.