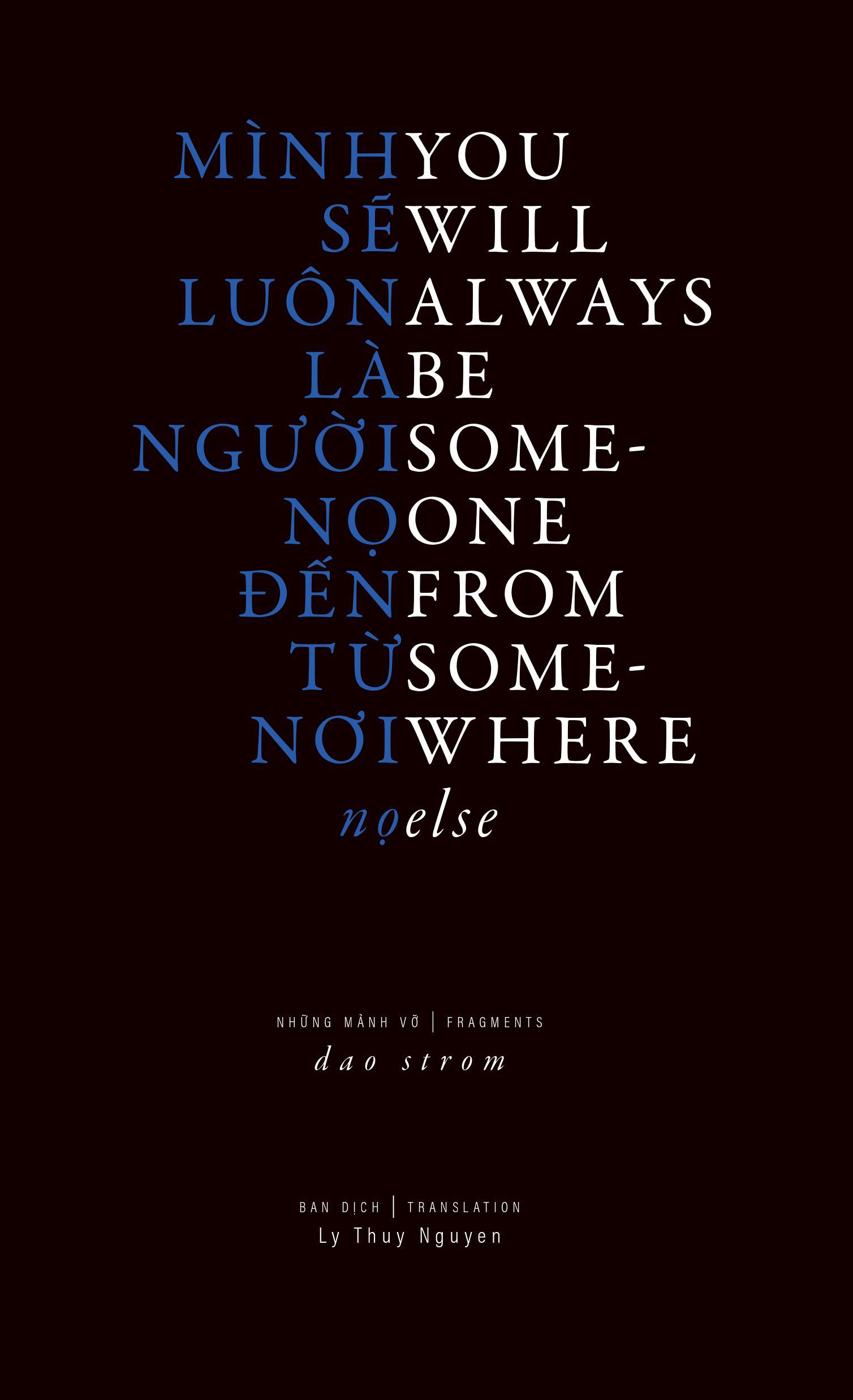

An interview with Portland multimedia artist, musician and poet Dao Strom, whose work explores echoes of history and a sense of non-belonging.

What events inspired you to write You Will Always Be Someone From Somewhere Else?

It is hard to point to any single event or set of events. I am interested in the echoes of history, the reverberations of it, which we might call memory but is never exact memory. Refugee exodus, Vietnam, the long shadows of war and displacement, divisions, being caught-between—these are continuing sources and places I write from, and for.

What is the purpose for writing the book in two languages, and what do you hope to accomplish/convey by doing this?

I have always as long as I can remember felt a sense of non-belonging, or longing, and a certain weight about the past, that is not applicable just to Vietnam but maybe to the world of humans in general. Language is both a tool of connection and causes disconnect, as I see it. Knowing language is supposed to give you access to meaning and understanding; but then does not knowing language (my lost Vietnamese, for instance) mean I cannot ever really know what it means to be Vietnamese? The bilingual book for me is both a process and a project—to wrestle with questions like this one, and to re-engage with the language, in the ways I can.

Can you tell me about the photos in the book, and why they are in fragments? What does this symbolize?

The photos are from return trips to Vietnam (1996 and 2014), from my own family archives growing up in northern California, and some documentary found photos sourced from the public domain and from war-era journalists. In particular, there are a couple photos drawn from the newspaper my mother and birth father were publishers of in Saigon during the war era. I play with fragmentation to play with the notions of framing and re-framing and also failing to frame—refusing to frame—events or memories. Sometimes I let pictures fall off the page or leave out definitive information also because this is how I feel about narrative—I don’t believe the whole story can ever really be told, or can fit on the page.

Why was it important for you to use photography to tell your story?

I think being Vietnamese American sort of necessitates contending also with image—how imagery has shaped our representation in the western imagination and in the so-called history of being Vietnamese in America. I am leery of the ways that even the most well-meaning documentary photography—especially of non-white subjects—subtly figures that group’s status or identity in the West: Vietnamese, and Asian bodies in general, are perceived foremost as victims in need of rescue and assimilation. Making art that investigates imagery and also narrative—the myths we believe about ourselves and others—is important to me. But since it can also be problematic to be re-handling historical images all the time, I also believe in the importance of creating new imagery, too.

The first time I went back I was 23. Since I’d left as a 2-year-old, I had no memories of Vietnam or of leaving. So the biggest thing I learned, on that first return, was that collective consciousness and inherited trauma are very real things.

Sometimes there is an image with a missing part that is brought into focus on a different page. What does this represent?

Memory is definitely a factor in the practice of fragmenting. I see memory as made up of nonlinear sequences, leaps of association, dissociation, fragments, things I actually remember and pieces I have been given or have absorbed. Memory is also esoteric and fallible, subject to so many variables. There is no whole or “true” picture I am trying to reconstruct or allude to, in the end.

You describe your mother as eager to leave Vietnam after the Fall of Saigon while your father “felt sick at even just the thought of the word. Leave.” How has your parents’ vastly different values and perspectives on change affect your life? Do you relate to one parent more than the other in that sense?

The decisions my parents each made were shared by many at that time—some South Vietnamese people made the decision to leave, some decided to stay; but also many had no choice at all, for how things turned out for them, no matter what they wished to choose. I can’t say that I am more one way or another, but I observe my position as being between and of both types of action… My life would not be what it is today—with all the privileges, complicities, and complications of being an American Vietnamese—if my mother had not left. I respect them both and also feel that perhaps both decisions—to stay or go—harbor the same deep conflict and sense of paradox that many Vietnamese people have had to live with.

What made you want to return to Vietnam in 1996? Did you gain or learn anything about yourself by going back?

The first time I went back I was 23. Since I’d left as a 2-year-old, I had no memories of Vietnam or of leaving. So the biggest thing I learned, on that first return, was that collective consciousness and inherited trauma are very real things. Even though I didn’t personally remember anything about Vietnam or the war, the return was still quite emotional for me. In 1996 in Vietnam it was something I felt palpably, in the air, that collective sorrow.

Does the current political climate shape your views on immigrants, refugees, and the notion of home? If so, how?

I hope the current heightened concern for refugees and their situations—unfortunately inspired by the present climate—may also lead to more openness and support for people from refugee backgrounds to enter into decision-making and greater self-agency in this society. I think that is where change may start to happen, when more people with these diverse backgrounds and beginnings have the power to make things happen for themselves and their communities.

Do you have anything else in the works?

I made a video recording of a sung-poem called ‘Traveler’s Ode’ that I consider a companion piece to You Will Always Be Someone From Somewhere Else. It was filmed in a really unique location, a (nonfunctioning) nuclear power plant cooling tower in Washington. It debuted as an experimental poetry work in Poetry Northwest in January.

Photo by Dao Strom.

Lauren Kershner is a freelance writer based in Portland, Oregon. Her work has been published in Portland Monthly, Willamette Week, Pearl Magazine, and Travel Portland. When she’s not writing at home with her cats, she can be found performing on stages with her piano as a solo singer-songwriter.

Dao Strom is a writer, artist, and musician whose work explores hybridity through melding disparate “voices”—written, sung, visual—to contemplate the intersection of personal and collective histories. She is the author of a bilingual poetry/art book, You Will Always Be Someone From Somewhere Else (Ajar Press, 2018), an experimental memoir, We Were Meant To Be a Gentle People + the music album East/West (2015), and two books of fiction, The Gentle Order of Girls and Boys (2006) and Grass Roof, Tin Roof (2003). Her work has received support from the Creative Capital Foundation, National Endowment for the Arts, Precipice Fund, Regional Arts & Culture Council, Oregon Arts Commission, and others. She is the editor of diaCRITICS and co-founder of the arts collective She Who Has No Master(s). Follow her on Twitter at @herandthesea.

.

You can view Dao Strom’s multimedia work On an Open Field — a mix of photographs, music, and text — online here at Cascadia Magazine.

.

.

.

If you appreciated this profile of an artist doing great things in the Pacific Northwest, please consider becoming a supporting reader of Cascadia Magazine. Please visit out donate page to make a contribution. Thanks!