Kristen Millares Young will be reading in Cascadia Magazine’s Seattle Writers + Artists event at 6:30 pm Tues. December 10 at Vermillion in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood. More details here.

1.

Biking up Beacon Hill never makes you feel good. First there’s the right turn up Alaska, waiting at the MLK intersection for the light to change, and then it’s time to pop up in the pedals and give it all you’ve got, which isn’t much by the time you hit the incline on the other side of the boulevard. Here, the road begins its ascent, and you’re peddling, and for a while, you think, I’ve got this, I’ve totally got this, but you’re slowing, still standing in the pedals, and now you’re downshifting, and the blackberry bushes aren’t flashing by anymore. You can see their thorns and the matted trails made by people looking for a patch of land to live on, and you’re in first gear, nowhere to go but up. You’re going, but now you taste the diesel, and the sidewalk’s gone to shit, and that family left their recycling bin in their driveway again, and one weave is enough to make you wobble so you’re sitting, sucking wind and fumes and hawking loogies at the top of the hill, where everyone looks at you, shaking their heads, glad to be in their cars.

2.

Cresting Beacon Hill is just the beginning, because this was before the mayoral campaign about bike trails, and the only paint on the street marks the potholes. You try not to notice how close the cars come, and you’re focusing on the golf course with the small stooped men lugging their clubs, and by this time your clothes are clinging, and it’s no good to pretend that half that isn’t sweat, which is the great fallacy of wearing rain gear to exercise. Your jacket opens when you lean over to change gears, and you can smell yourself, glad there’s a shower at the newsroom where you won’t have a job much longer. But you don’t know that now, so as the Escalades roll past, trailing bass and blunt smoke, you inhale, hoping to get high so the deadlines won’t make you sick to your stomach again. When you get to the intersection at 15th, you hop onto the sidewalk to beat the light, and soon you’re back on the road, flying past parked cars – please don’t open your door, please don’t open your door, please don’t open your door – you want to live though it’s raining and you’re screaming down the 12th Avenue bridge, and then there’s Smith Tower and the Sound. Seattle shows you what she’s got through the mist and rain, and you’re glad to be alive though it’s wet and cold and you’re only halfway there.

3.

You take a left on Jackson because although the bike map says Dearborn you know that isn’t the best way. Here, stop signs are suggestions, and some people drive like every time is the first time. So you take Jackson, and that means carts full of oranges, that means carts full of fish, that means buses and buses, and then that lady is riding your ass like she wants to touch it, her bumper so close you can feel the heat of her engine, and when you finally get to the light, you do it, you give her the finger and scream stay off my ass, and for the next six blocks, she’s wagging her finger at you because you just disrespected an elder. Your abuela would be ashamed. For the rest of your ride, you smile and nod at everyone you see, so they’ll feel acknowledged and you can stop feeling like you killed something small.

Newsrooms are like that; they make you lose sight of everything but the need to feed the paper, and now, this digital coalmine that eats words but never digests them.

4.

The Alaskan Way Viaduct is dangerous, everybody knows it, the next time the ground shakes it’ll smack flat as a pancake but the oozing berries will be cars. Beneath it’s dark even in full daylight, and it smells like rape, and you know that’s what happens here because you’ve heard it before, because you’ll hear it in ten minutes: where’s the rape story? shouted from the breaking news editor, and the retort, open your eyes, RAPE16 is in already, and the bitterness of trading trauma this way will grind you down until you decide to wear earplugs that blacken with time. But for now, you’re cruising along the bike lane, and you have to remember to slow down at the intersections because that’s where they’ll get you. You emerge at the port and hope those people don’t see you because they started hating you after the federal investigation, and you have nothing to tell them but, this is my job, to expose your incompetence and corruption, but not until after coffee and a shower.

5.

At first, we didn’t know what was happening. It was late, and you were tired, and that was enough to explain the headache, because you’d been choking down coffee since 9 a.m., and it was 10 p.m now, and that had become your new normal. Newsrooms are like that; they make you lose sight of everything but the need to feed the paper, and now, this digital coalmine that eats words but never digests them. So you ignored the feeling of pressure, ignored the giant hands clamped around your brain and beginning to squeeze like you had autism and needed to be calmed down, something you learned to do when your nephew banged his head on concrete. But there’s no one above you, and now you can smell them, these strange creeping chemicals coming from the air vents, and you bring it up to the managing editor, and he says, they’re trying to smoke us out of here like rats.

You got mad at him; he was not “us,” he was the boss, and he needed to do something, it’s not enough to commiserate, he needed to lead, and only later, when the paper closes down and the videos of the announcement show him drop his face in his hands like a pebble, show his eyes in despair and humiliation of hearing the news alongside his reporting staff, that you realize it was “us” all the time.

6.

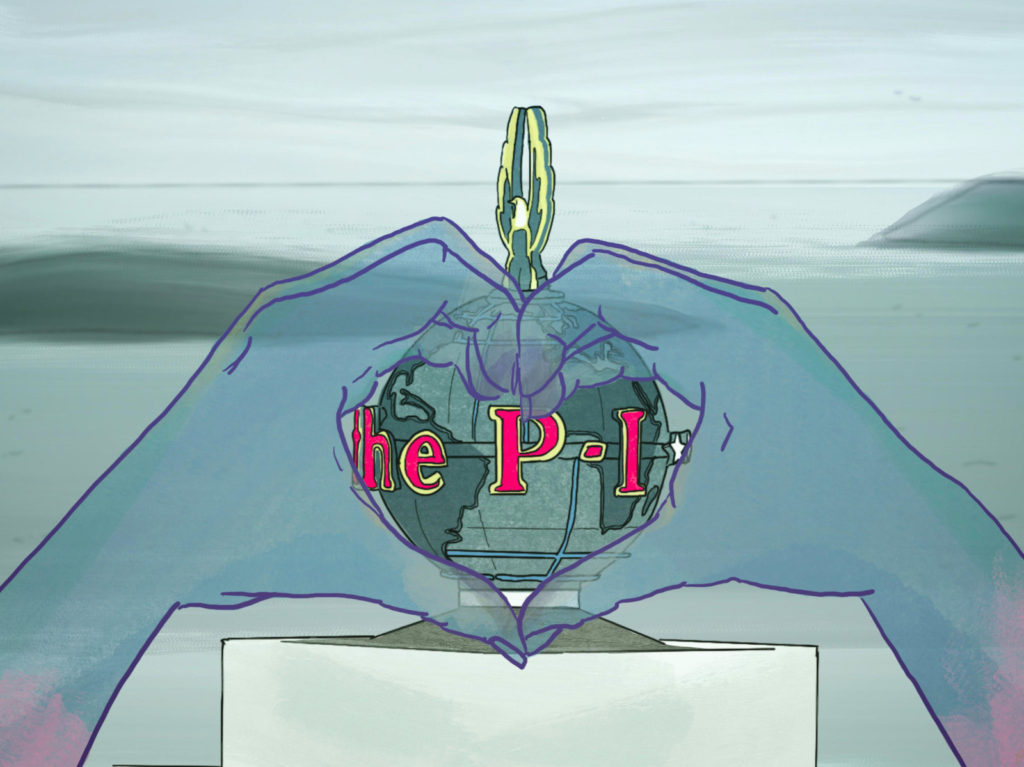

You used to feel your heart lift when you saw the globe turning on the newsroom’s building, but today, when you saw it on the bus from Belltown, it clawed you like a fork gone rusty. Hearst can’t make a profit though it busted the union, fired the reporters and farmed out content production to citizen bloggers. You don’t blame them. Business is business. You’re glad the weight of history will remind them that their poor decisions killed the paper, the oldest business in Seattle, printing all the way back from 1863. They couldn’t just eviscerate a news staff and expect the skin and bones to keep walking. You think of the 700 stories you wrote for them. It took you seven years to produce your first novel, and you wonder whether you have found your calling or are evading your journalistic responsibility to the world, because you were one of the P-I’s best reporters, and that’s not something you’ll apologize for saying. You carved yourself into a hollow just to do it. Anyone who’s made themselves sleepsick knows what you are talking about.

7.

It’s funny how time does its work on you, gnawing through your skin like dust mites, adding pounds to your mattress by the time you’ve bought a new one. When you see your reflection wobble in the glass of the old P-I building, your hips distorted like a funhouse mirror, the only thing that holds steady is the stroller, which makes you feel things you won’t put into print. You’ve tried to be the one to compose essays while breastfeeding. Sometimes you’re so tired all you can do is check Facebook.

Okay, it was raining, and you were unhappy, but there was fellowship in misery. Why else do you think family is family? So there, on that deck, you fold up your decision to move on and wedge it beneath a cigarette butt stuck in the cracks between the concrete tiles, which ruined more stilettos than you care to count.

But hey, let’s not blame the baby. It used to be you could blame your job, then it was your nerves, or lack of nerve, the words dripping from you slow as an IV, and you always checking the patient, taking her pulse, fluffing the pillows, pushing food, pushing drugs, pulling the shade only to let it fly flapflapflapping to the sky. Maybe a walk would ease these jitters, so you bundled up the baby and off you went, and now you’re playing memory palace to pretend you’re doing something more than using your child to buffer the soulless demands of your talent.

So there, in the globe, you hide your parable of unfettered ambition, beneath the red letters that read “It’s in the P-I” but not under the three stars that follow. No, there, beneath the middle star, you tuck the lament of the woman who forsook motherhood for a career that never cuddled her back. There, on the tiny concrete deck overlooking the coal trains, a deck not big enough for hopscotch would fit you and the columnist who bummed you his smokes, shuffling your feet and squinting through the mist slanting hard and sideways. Okay, it was raining, and you were unhappy, but there was fellowship in misery. Why else do you think family is family? So there, on that deck, you fold up your decision to move on and wedge it beneath a cigarette butt stuck in the cracks between the concrete tiles, which ruined more stilettos than you care to count.

And here is this baby, practiced in the art of companionable silence, and so what if your attention self-destructs every fifteen minutes. Your talent needs a timer and always has. He’s beautiful. Between his toes you’ve tucked your latest poem. Between his fingers you’ve placed your newest prose. Beneath the soft crescents of his nails you’ll place nothing because that might hurt him. But there, in the longest fold of his fat thighs, there’s your novel, and he’s sweating all over it, it takes on that sheen of a hatband and smells like sour cherries, it roils like a powdery sea, and only in loving do we complete ourselves, only in giving are we renewed.

Artwork by Sarah Salcedo.

Publication of this essay and art was made possible by a generous grant from the Seattle Office of Arts & Culture.

Kristen Millares Young is the author of Subduction, a novel forthcoming from Red Hen Press on April 14, 2020. An essayist, journalist and book critic, Kristen is Prose Writer-in-Residence at Hugo House, a nonprofit home for writers. Her writing has appeared in the Washington Post, the Guardian, the New York Times, Poetry Northwest, Joyland Magazine, Hobart, Crosscut, Moss, Seattle’s Child, Proximity, City Arts, Pacifica Literary Review, KUOW 94.9-FM, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Miami Herald, the Buenos Aires Herald and TIME Magazine. Her personal essays are anthologized in Pie & Whiskey: Writers Under the Influence of Butter & Booze (Sasquatch Books), a 2017 New York Times New & Notable Book, Latina Outsiders: Remaking Latina Identity (Routledge) and Advanced Creative Nonfiction: A Writer’s Guide and Anthology (Bloomsbury of New York and London, March 2021). She lives in Seattle. Follow her on Twitter at @kristenmillares.

Sarah Salcedo is an author, illustrator, and was formerly marketing director of Hugo House, a literary center in Seattle, before leaving to launch Tall Firs Productions as well as produce and direct their first feature film, Promised Land , an award-winning social justice documentary that follows two tribes in the Pacific Northwest– the Duwamish and the Chinook,–as they fight for the restoration of treaty rights they’ve long been denied. Follow her on Twitter at @SarahSalcedo.

If you appreciate great writing and visual art like this, please consider becoming a supporting reader of Cascadia Magazine. You can make a contribution at our donate page.

One comment

Comments are closed.