After the glasses have been put in the sink, the bottles put back on the shelf. Or after the receipts have been tossed out and your shoes kicked off or paired up and put where they go. After a fitful sleep. After the heavy helmet of headache. After the burnt toast or greasy burger. After the hot, black coffee. After the large glass of water to take the 2 ibuprofen. After going back to bed. After trying again.

It’s there. The haze of memory and the ache of feelings we can’t quite remember. Things we may have done or things that may have been done to us. Trying to remember clearly after a night of heavy drinking is so similar to trying to remember clearly the ways alcohol seeped through our childhoods.

All of this hangs over us.

Memories are cubes of ice. They seem so crystal clear, so tangible. And then they melt, dilute whatever drink you put them in. You think you have a hold on them, then they change shape, melt, slip from your hand, shatter on the floor into hundreds of pieces melting into tiny, unseeable puddles. Like tears. Maybe we are meant to let them go?

“And when, at last,

we let them go we start to pity them,

attend their needs: I almost have to think

to keep my own heart beating through the night.”1

No matter how many times I try to hold these memories close, inspect them, store them, they slip from my grasp. If I hand these ice cubes to you, what happens?

You can tell me a story from your childhood. You can tell me stories of drink and danger. You can hand me ice cube after ice cube. My hands are too warm and my mind cold. There is no in between. Look what you gave me, only water now. All I have is a puddle I’ll claim is the ice you gave me.

I have no talent for memory. Regardless of how I try, I fail to remember so much. Isn’t that why we mourn? Because we know the death of a person is a loss of both what will be and what was. Was she right handed or left? Did she like roller coasters? Every trivial detail becomes momentous once the beloved is gone.

“I’ve forgotten more about that girl than you’ll ever know.”2

I know a father who can tell me the exact same thing. I believe, if given a chance, he could build an empire of forgetting.

I, too, am forgetting so much, so quickly. If you walked right up and handed me a cube, I wouldn’t know what to do with it. I would let it melt through my fingers. I would only remember the way it all slipped out of my hands, even if I tightened my grip. Especially.

Doesn’t it seem that the tighter we hold something, the harder and quicker it leaves? Like sand through the belt cinched waist of the hourglass. But even the cold, empty space left is something. It’s feeling breath on your neck and turning to find nothing but the empty kitchen. It’s hearing a bell ring, but being in the middle of a field in the middle of nowhere off a dirt road. It’s finding an empty glass on the counter in the morning and not knowing where it came from. The spaces left become a collection of tryings.

Trying to remember _______.

Trying to solve for x.

Trying to find something we can no longer name.

“Your life is one vast swirl of memory, and you want to let it ferment and distill like a good Scotch whiskey.” And good Scotch sits so long in its barrels that some is lost to the air, “the 2% that evaporates, the part they call the “angel’s share.”” 3

The angel’s share. Somewhere an angel wrestles with our evaporated memories. Somewhere an angel wants to know why we can’t hold on to these things. At least Scotch keeps the angels warm, gives them spicy breath, helps them forget.

“Every angel is terrifying,” Rilke wrote. Every memory, too, if you’ve led a certain kind of life. I must admit my life is little terror and mostly dull in the most pleasing way. I am nearing the age where I will have more to look back on than look forward to. I carry a few regrets like raw onions, a sort of controlled and concealed crying. What have I done, and to what end?

“In my life will I make a difference? In my death will I be missed?” 4

If someone holds the memory of me in their hands, if I am written on water, what are the words left to read?

(Dear Mnemosyne, be kind.)

I can’t predict the future despite the fact the future is mostly a series of results based on the choices we make now. What I write at this very minute, what I choose to drink. All of it digging a pathway to you. In what future will we meet again?

“Oh that I could shrink the surface of the World

So that suddenly I might find you standing by my side!”5

We can toast in the new. We can mourn the past. Maybe we are sitting in some future with more war. Maybe one with peace like a cube in its hand that melts, yes, but slowly.

Friend, I have something of great importance to tell you. My youngest daughter recently said when she grows up she’ll remember me laughing.

I raise my glass to that laugh that echoes of you. I raise my glass to her dimple. I raise my glass to all our daughters. I raise my glass to every laugh they remember long after we melt in their hands.

This sounds sadder than it is. I turn once again to poetry, to the echo of what words might mean.

“And it occurs to me that what is crucial is to believe

in effort, to believe some good will come of simply trying…” 6

And haven’t we done at least that? Tried to leave something more than ice cubes. Tried to leave laughter and the way the light falls across a pillow and the way sometimes dust in the sunlight looks like magic.

1 | from Andrew Hudgins’ poem “What Light Destroys.”

2 | from Scott Spencer’s novel Waking the Dead.

3 | from Judith Kitchen’s book length mediation on memory, Circus Train.

4 | from Crywank’s song “Memento Mori.”

5 | from Wang Chien’s poem “Hearing That His Friend Was Coming Back From the War.”

6 | from Louise Glück’s poem “The Empty Glass.”

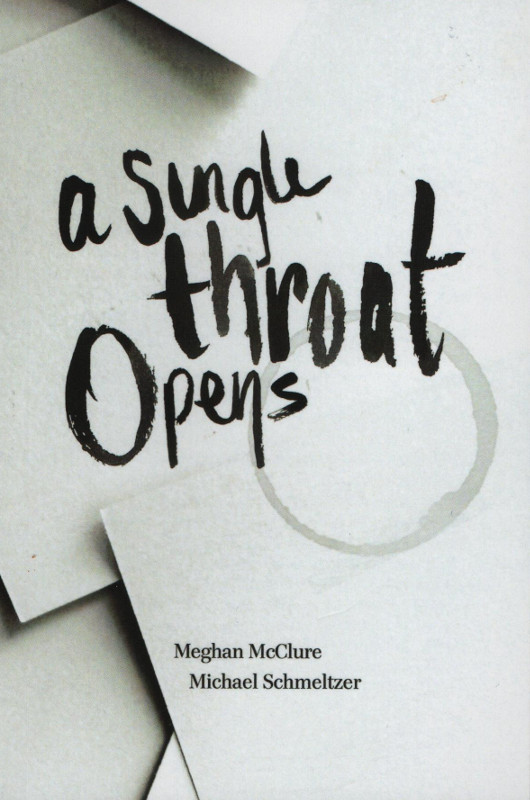

This hybrid essay by Meghan McClure and Michael Schmeltzer is a new postscript, a literary “hangover” to their book A Single Throat Opens (Black Lawrence Press, 2017).

Exploring both the pain and allure of alcoholism, A Single Throat Opens is book that defies genre, a lyrical series of vignettes, memories, allusions, and imagined scenes. Written in a series of email exchanges, Meghan and Michael kept the entries anonymous to preserve a shared narrative voice. The memoir is honest and vulnerable in its portrayal of the way addiction harms people, and yet it’s also filled with immense love for those who struggle.

Jill Talbot says of the book, “At times, it’s impossible to discern between the two voices, so tied are they in their reverence and reckoning, their lies and longing, their desire for the burn of drink mixed with the shared fear of it in their blood. The lyricism of A Single Throat Opens will make every listener thirsty, parched on the last page for more. This book is a yearning.”

Continue below to read an interview with Meghan and Michael about the creation of A Single Throat Opens.

An interview with Michael Schmeltzer and Meghan McClure

So what was the impetus for the book? How do you two know each other?

Michael and I met because of poems. We were both fortuitously published in the same issue of Superstition Review and Michael reached out after he noticed that I was attending the same MFA he had graduated from. Turns out we lived only 13 miles away from each other and we met over coffee on a typical dreary Seattle morning with his 3 year old daughter in the stroller beside us. My friendship with him is, I believe, my fastest friendship ever. We have so much in common it seemed impossible. And one thing we have in common is that we both have family members who are or were alcoholics. We have a shared story of lineages marked by addiction. Writing together seemed like the natural path our friendship would take. And we both had this big story we’d never told on the page. It all happened so naturally it’s hard to answer this question. But I can say: without the safety of our friendship, this book could not have been written.

It’s interesting how rarely writers work together collaboratively. How the did the process of writing this book go? How long did it take to write the first draft of back-and-forths. Was there much editing or revision afterwards? Does it feel like a conversation, or is there a different word you would use to describe it?

It was a fairly organic process for us. I’d write for one week, pass off the piece however far I’d written, then Meghan would sit with it for a week and work on it. I think in total it took maybe a year? Year and a half? And that includes a hiatus Meghan took, a “crisis of theory” as she called it, in order to reassess some of the events in her life, past and present. Writing collaboratively with Meghan is probably the most painless writing I’ve done, to be honest. It feels akin to an intimate conversation as well as a confessional at time, a place where I can just lay down whatever is on my mind with no fear; I know whatever I write will be reflected on, reflected back, in surprising, elegant ways. And as a reader, it’s a great pleasure to read new work by someone you admire. And as a writer, it’s a great pleasure to be read by someone you respect, whose mind inspires you. We didn’t edit or revise too much as far as I recall, but I did sometimes splice my sections into hers in order to further muddle the mixture, to blend our voices even further.

I really like how there’s no demarcation of who wrote each vignette. How does writing anonymously change your voice, if at all?

This book was, for me, quite scary to write. I was facing a lot of things I had not fully dealt with – and in fact, I had to take a break from working on this to deal with some things that came out of this project. Writing with someone I admire not only as a writer but also as a human, and writing sort of anonymously actually freed my voice quite a bit. I think I was able to speak more strongly from my own voice. It wasn’t so much a hiding in the text as it was a bolstering by this other brave and powerful voice from a human I care about so deeply. Because of the similarities between Michael’s life and my own, it was even easier to meld our voices. It felt so much like a conversation where we picked up each other’s sentences, talked at the same time, nodded together, took deep breaths and long sighs together. I don’t know if writing this way changed our voices as much as it amplified them.

“I’m addicted to not needing.” How are addiction and personality similar? Can we change ourselves, or do we just accept who we are, who are parents are, what the world is, and swallow it down? One of you mentioned Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art” as a manifesto for tolerance. Maybe it’s related, this idea that you can build up to any loss and then write it down?

I’m an expert in neither addiction nor personalities so hesitate to say too much. I imagine they can magnify or minimize the other depending on which end of the binoculars you look through. In other words, I almost see addiction as an improper amplification/minimization of personality, perhaps. Again, I want to be extremely careful in how I talk about addiction and people who battle addiction. Ultimately, I want to ensure we never fail to recognize the humanity of an addicted person. Safe-injection sites is a topic Seattle has been tackling recently. It naturally elicits some strong reactions. I think if we could see acceptance as a way toward change (in yourself, in an addict, in a movement) rather than a way to end change we might all benefit. Writing about my family in this book has allowed me access to acceptance, which didn’t shut down hope for change but made room for it.

As for Bishop’s poem, I just love the momentum and almost inevitability of it. It brings to mind tolerance and rock bottoms. But the resilience in the poem sticks with me, the idea that we are stronger than we think, that we can master loss. What intoxicating bravado!

“Addiction requires no substance, only something to escalate, something to build until it collapses under its own weight.” How are intoxication and poetry related? Do you think addiction is necessary or inevitable?

I don’t know if intoxication and poetry are related in any way other than a changed state of mind. Except one is healthy and one isn’t. I won’t romanticize addiction. It breaks lives in so many ways, and for so long. But I think we all deal with our own addictions. I don’t think any of us are without our addictions. I think about this a lot. It’s something I can feel following me like a shadow, how easily we can slip into something like alcohol and how easy it can become to excuse it. How easy it is to say we have control of something when we don’t. I think, even if we think we don’t have any addictions ruling our lives at the moment, we are all one moment, one warm sip away from craving something for the rest of our life.

There’s a lot about lying in this book. “Maybe I really believe that it’s wrong to lie, and now I’m just playing a part. Maybe I lie about everything. Maybe I never lie. You’ll never know.” This book isn’t exactly a memoir, but even memoir is almost always an act of creation, of imagination. How much, if at all, do you feel compelled to be loyal to truth in this book, to what you remember?

I have been thinking a lot about truth, its relationship to poetry and creative nonfiction. I’ve said before poetry can tell lies in order to reach a greater truth but perhaps when writing this I wanted to tell the truth in order to reveal the greater lies, the denials, the things I’ve told myself in order to sleep better at night. I wanted this to be honest even as I contemplated dishonesties because so much of dealing with addiction in the family is about keeping up the fantasy that things are fine. And the confusing thing is…sometimes they are. There is so much love and happiness and laughter in my family. It would be a lie to say there isn’t. And yet.

I mentioned the collaborative writing process with Meghan at times felt conversational, at other times confessional. I was dedicated to truth in this piece because in many ways I am dedicated to my friendship with Meghan. I didn’t want to lie to her. So I wrote my truth through memory in hopes we would be even better friends.

Interview conducted with Andrew Engelson via email. Photo credits: alcoholic drink via Pxhere, photos of Meghan and Michael courtesy of the authors.

Meghan McClure lives in California. Her work can be found in American Literary Review, Mid-American Review, LA Review, Water~Stone Review, Superstition Review, Bluestem, Pithead Chapel, Proximity Magazine, Boaat Press, Black Warrior Review, among others. Her collaborative book with Michael Schmeltzer, A Single Throat Opens, was published by Black Lawrence Press and her chapbook Portrait of a Body in Wreckages won the Newfound Prose Prize and is forthcoming in 2018. Follow her on Twitter at @meghantmcclure.

If you appreciate great writing like this at Cascadia Magazine, please take a moment to make a donation. Your generous financial support helps pay creative people from across the Pacific Northwest a fair rate for their work.